Octagon Gallery

UCL Main Building

9am-7pm, Free

Discover more about Disrupters and Innovators, UCL's exhibition dedicated to remarkable women, whose lives and careers were shaped by what they learnt, taught and researched at UCL.

The exhibition curated by Dr Nina Pearlman is presented in two parts: a prologue called The Magic Fruit Garden, and Disrupters and Innovators, which features a number of women with connections to the university.

The stories in this exhibition reflect the long struggle for democracy in the UK and for gender equality in higher education. They provide insights into educational reform, advancements in science and art and social and political change in the world in which these women lived.

Some women were rewarded with professional recognition and personal accolades for their contributions to their discipline, culture and social reform. Others, despite equally significant contributions, received much less attention and reward. It falls to later generations to uncover their achievements and restore their reputations. Find our more about these women here.

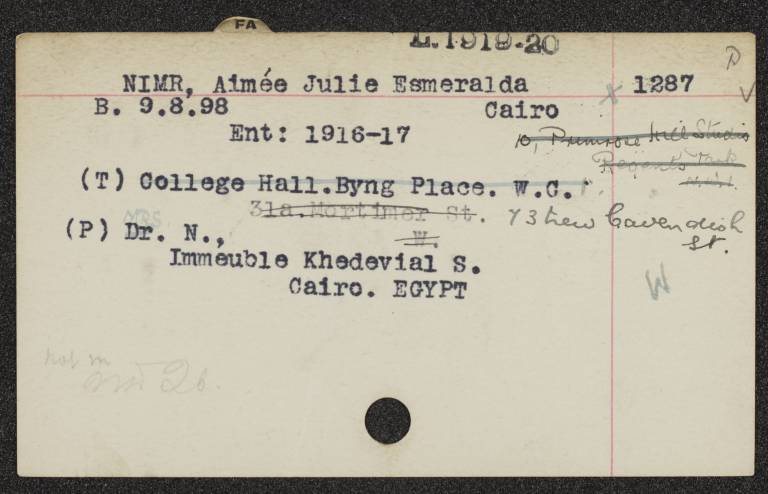

Student registry card for Slade student, Aimee Nimr (1907-1974). After graduating, Nimr became a driving force in the Art and Liberty Group founded in 1930s Cairo. Its members – Surrealist artists, poets and writers – aspired to connect art with social issues, particularly the impact of World War II on Egypt.

Exploring new disciplines

Disrupters and Innovators is displayed across four cases in UCL's Octagon Gallery. In the second part of the exhibition, each case addresses a different area of academic study: Archaeology, Art, Science, and Politics and Society. Visitors can explore how women pioneered new disciplines and their often interdisciplinary approaches.

- Archaeology

Archaeology was a new science at the end of the 19th century. The study of Egypt – Egyptology – was on the edge of this new science. It did not require the same formal qualifications, such as knowing Latin and Greek, demanded by more established subjects. As women were less likely to have these qualifications, Egyptology was easier for them to enter.

The attitude of the first UCL Professor of Egyptology, Flinders Petrie, was crucial to women’s advancement in this subject. Petrie helped to transform archaeology from treasure-hunting to a scientific discipline, and his collection is held at the UCL museum established in his name. Petrie's own career was made possible by the generosity and support of women, particularly his benefactor Amelia Edwards and his protégé Margaret Murray, who is featured below.

Murray enabled Petrie to make long trips to Egypt to carry out excavations, as she taught most of UCL's Egyptology classes. Her high profile as a scholar, teacher and advocate for women’s rights in turn contributed to the subject’s popularity with women. In 1907, Manchester University Museum received a rare collection of two mummies, complete with the contents of their tomb, and Murray worked to catalogue the objects. A year later she took part in the public unwrapping of one of the mummies to an audience of 500 with extensive media coverage.

Margaret Murray and team unwrapping the mummies of the ‘Two Brothers’ at Manchester University Museum in 1908. © Courtesy of Manchester Museum

“The shelf is not a comfortable place and I have no desire to be on it...

I look forward to working till the last."Egyptologist Margaret Murray aged 100, autobiography, 1963

- Art

The Slade School of Fine Art was founded in 1871. Teaching was grounded in the study of the human figure, setting the Slade apart from other schools. The admission of women to study alongside men formed another radical departure from established models. The Royal Academy followed suit nearly twenty years later, with other disciplines at UCL even slower to adopt a co-education approach: medicine was the latest in 1917-18.

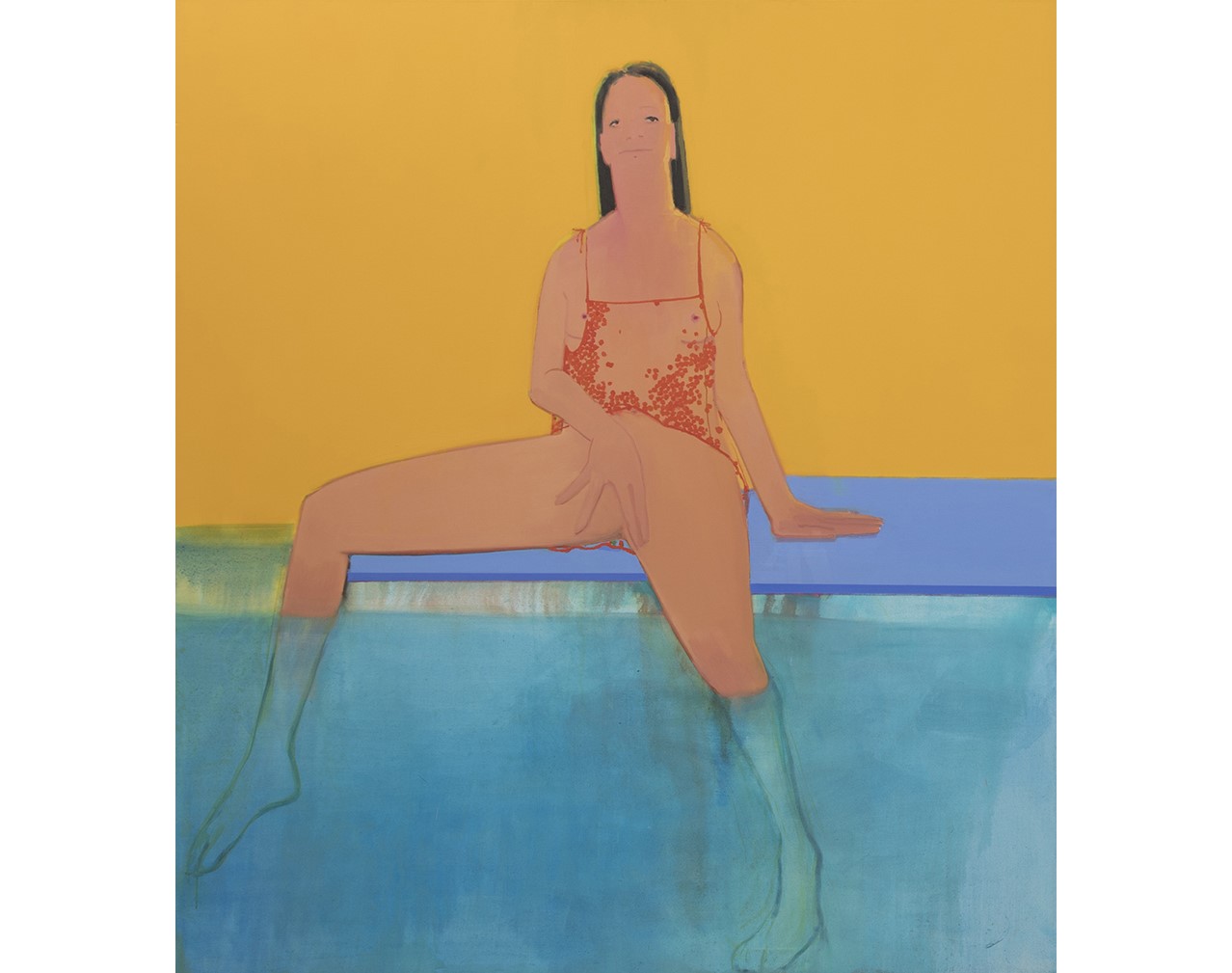

The Slade influenced women’s integration into wider College life and society, and many Slade women worked across disciplines or were involved in socio-political reform. Female students quickly outnumbered male ones at the Slade and their achievements were recognised by prizes. While 45% of the artists in the Slade Collection are women, many including Clara Klinghoffer (featured below), Winifred Knights and Aimee (Amy) Nimr in the exhibition, remain largely unknown today.

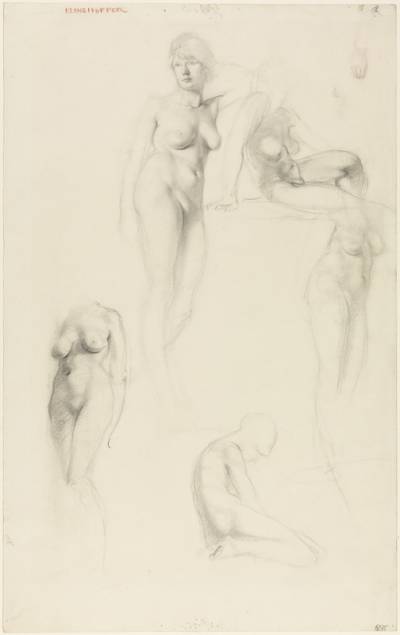

Clara Klinghoffer (1900-1970) was an Austrian Jewish émigré who enrolled at the Slade in 1918. A year later, she won second prize for Figure Drawing and received the Orpen Bursary for students who ‘intend to become Professional Artists’. Promoted by influential artists such as Sir Jacob Epstein and Alfred Wolmark, she presented her first critically acclaimed exhibition in 1919. Reviewers compared her to the grand master of Italian Renaissance, Raphael. Journeys of early 20th-century women artists like Klinghoffer are explored in the UCL Art Museum's 2018 exhibition Prize & Prejudice.

Clara Klinghoffer, Five Studies of a Female Nude, c.1918-1919, pencil. UCL Art Museum 6075 © The artist's estate

“Girl Who Draws Like Raphael - Success at 19"—Review of artist Clara Klinghoffer’s exhibition in The Daily Graphic, 1919

- Politics and Society

Women’s and workers’ rights, prison reform, education and Irish independence were key social and political concerns of the early 20th century. Women working across the sciences and humanities at UCL became forces for change in these areas, often alongside significant contributions in their own disciplines.

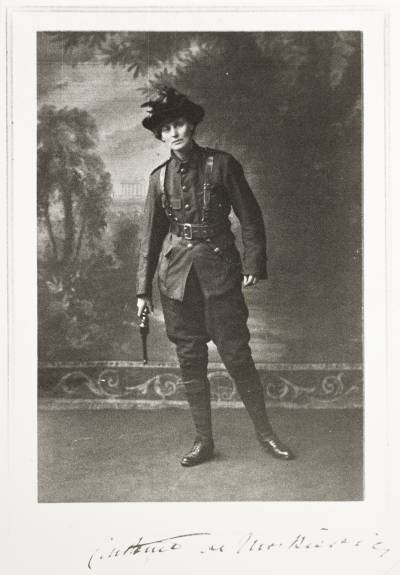

Constance Markievicz (née Gore-Booth) was the first woman elected to the British House of Commons in 1918. She became an MP for a Dublin constituency while in prison, along with many Sinn Féin MPs who were political prisoners at this time. As with other Sinn Féin MPs, then and now, Markievicz did not take her seat in Parliament.

Markievicz previously studied at the Slade School of Art and she became increasingly involved in the suffrage cause during this time. Despite her aristocratic background and marriage to a Polish count, she felt passionately about art and workers’ rights throughout her life. She was imprisoned and sentenced to death for her part in the 1916 Easter Rising against British rule, but was later released under a general amnesty.

Digital reproduction of studio portrait of Countess Constance Markievicz, Keogh Brothers Ltd, c.1910-1927 NPA POLF206 © National Library of Ireland

“...When I urged that the women’s suffrage movement had gone too far to be stopped he disagreed."—Reformer Isabel Fry reflecting on a conversation with retired Judge Bacon, known for his anti-feminist views, 1911

- Science

y the 1990s, the scientific community had started to uncover the missing histories of women scientists. Disciplines such as botany and geology had long traditions of amateur contributors, often women, alongside professionals. The uncertain career paths offered in emerging scientific disciplines were often less attractive to men, and new disciplines often had less defined entry paths, or involved applied research that carried less academic prestige. These circumstances all provided opportunities for women to further develop research and careers.

Dame Kathleen Lonsdale (née Yardley) (1903-1971) is pictured below. She was one of the first two women to become a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1945, and the following year she founded a research group in Crystallography at UCL. In 1949, Lonsdale became the university's first female professor and she received both the Royal Society’s Davy Medal and a DBE in under a decade.

During her lifetime, Lonsdale worked with influential professors such as William Bragg and Christopher Ingold. Nobel Prize winners Bragg and his son Lawrence pioneered the use of X-rays to determine crystal structures, and Lonsdale applied this technique to the petrochemical benzene, confirming its long-disputed structure. As a scientist she worked at many institutions but UCL was her first, last and longest. UCL marked her legacy by naming a university building in her honour, the only building to be named after a women. The refurbished Kathleen Lonsdale Building is located on UCL’s main Bloomsbury campus.

Kathleen Lonsdale with crystal models, photographer unknown, c.1946. Courtesy of Professor Ian Wood, UCL Earth Sciences

“...questioning of the established order is the hallmark of the true scientific outlook..."—Crystallographer Dame Kathleen Lonsdale, The Melbourne Herald, 1966

Behind the exhibition

Disrupters and Innovators is part of Vote 100 at UCL in 2018. Find out more about the background to this exhibition below:

- The history of women at UCL

This exhibition is part of UCL's year-long Vote 100 programme, which marks the centenary of the Representation of the People Act that granted the vote to some women over the age of 30 in the UK.

Beginning in the 1860s, UCL experimented with providing classes for women. From 1878, women could study alongside men and receive University of London degrees: the first time this had happened in the UK. It was not until 1918 that new legislation allowed the first women to vote in the UK. This was part of wider electoral reforms accelerated by World War I. Ten years later, women received equal voting rights with men. This process was a backdrop to the lives of female students and researchers at UCL and beyond in the early 20th century. However, co-education was not adopted in all subjects and female students and staff continued to face many obstacles.

The UCL Vote 100 programme reveals the impact of the pioneering women who built the university, and imaginatively explore the battles still to be won. Find out more about UCL Vote 100 here.

- Working across UCL

This UCL Culture exhibition is curated by Dr Nina Pearlman, Head of UCL Art Collections,who also produced this interpretation text.

Exhibition produced in association with:

Maria Blyzinsky, Museum Consultant, The Exhibitions Team

Victoria Kingston, Interpretation Consultant, The Exhibitions Team

Angela Scott, Senior Graphic Designer, UCL Digital Media

Dave Bellamy, Display Technician, Chiltern ExhibitionsUCL Culture would like to thank the following people for their support with the exhibition:

Society: David Blackmore (UCL Slade School of Fine Art), Dr Georgina Brewis (UCL Institute of Education), Dr Claire Robins (UCL Institute of Education)

Archaeology: Dr Emma Libonati (UCL Petrie Museum)

Art: Helen Downes (UCL Art Museum), Grace Hailstone (UCL Slade School of Fine Art)

Science: Deborah Furness (UCL Library Services), Lesley Hall (Wellcome Library), Dr Jenny Wilson (UCL Science & Technology Studies), Professor Ian Wood (UCL Earth Sciences)Thanks are extended also to:

UCL Art Museum, Grant Museum of Zoology, Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, UCL Geology Collection, UCL Pathology Collection, UCL Institute of Education Archives, UCL Library Services, UCL Records, UCL Special Collections UCL Special Collections, and UCL Slade School of Fine Art for their generous loans.

Close

Close