Contents

1. Executive Summary

Section 2 describes the LEADERS Project's main deliverables. These are a set of tools which implementers can use to build on-line archive applications and a demonstrator application to illustrate the potential of these tools. This section highlights LEADERS' belief in the importance of listening to users in the design of new technologies and explains that the report is based on results gained from testing the demonstrator application with a representative sample of archive users.

Section 3 provides further background information on the LEADERS tools and demonstrator application.

Section 4 gives details on the methodology for recruiting the representative sample of archive users and gives information on the participants' profiles including their motivation for using archive material, primary research interests, and familiarity with various aspects of archive based research.

Section 5 details the results gained from the testing sessions. These are organised in relation to the users responses to the various screens within the demonstrator. Where possible, the responses are analysed in relation to the participants' profiles to build a picture of how different types of users vary in their perceptions of the utility of the demonstrator.

Section 6 summarises the main findings and concludes by suggesting that future implementers of the tools can use the results as a guide in the development of their own applications to ensure that their end products meet the needs of their particular target audiences.

Back to top2. Introduction

Research undertaken by the LEADERS Project has been focused on exploring methodologies for providing integrated user access to archive material via the Internet. This has led to the development of open-source tools that can be used by Archivists to build on-line applications where digital representations of archive documents are presented alongside contextual information from finding aids and authority records. A demonstrator application has also been built to illustrate the potential of the LEADERS tools, and to act as a starting point for gathering feedback on how archive documents can be effectively displayed and delivered to users in an online environment.

From the outset, LEADERS has recognised the importance of understanding end users when developing new technologies. Our own interaction with users has centred on gathering a representative sample to take part in sessions to test our demonstrator application. During these sessions, the participants were able to engage with the demonstrator before being involved in moderated discussions on its strengths, weaknesses and potential for further development.

This report is based on the results from our user testing of the demonstrator application. It is hoped that potential implementers of our tools will use our findings as a guide in the development of their own applications to ensure that their end products meet the needs of their particular target audiences.

Back to top3. Background

The over arching aim of the LEADERS Project has been to enhance online user access to archive material. In practice, this has been achieved through the development of tools based on Extensible Mark Up Language (XML) technologies that enable the delivery of transcripts and images of archive documents alongside appropriate contextual information from archive finding aids and authority records. The LEADERS tools are flexible, extensible and adaptable to enable their use on multiple projects and with a wide variety of archive source materials. The tools are built on standard methods for encoding texts (Text Encoding Initiative); digital images (NISO Mix); finding aids (Encoded Archival Description) and authority records (Encoded Archival Context). As such, they consist of a set of XML DTDS and Schemas based on these encoding standards as well as indexing utilities, a search engine and web services.

We have developed a demonstrator application as an instance of what can be created using the LEADERS tools. This can be accessed via the LEADERS home page (www.ucl.ac.uk/leaders-project) by clicking on the link to the demonstrator application. As test material, the demonstrator is based on 17 documents from the George Orwell Archive and the University College London Archive both held at University College London. It therefore contains:

- 2 encoded finding aids (for the George Orwell Archive and the UCL Archive)

- 17 encoded transcripts

- 54 encoded authority records

- 114 image files

The demonstrator has been constructed to meet three main purposes:

1. To show the potential of

having transcripts of archival documents presented alongside digitised

images and contextual material, and to obtain user feedback on these

functions.

2. To serve as an example of

an application based on the LEADERS tools

3. To illustrate the use of industry standard, open source components each

of which can be modified or extended in its own right.

The application itself consists of a series of welcome, search input and results screens in the form of XML and XHTML documents displayed via a set of stylesheets and scripts. Examples of screen captures from the demonstrator are included in this report where appropriate.

A detailed account of the underlying architecture and technology of the LEADERS tools and demonstrator application can be found on the LEADERS Architecture and Technology Pages.

Back to top4. Methodology

4.1 Recruitment of users

The LEADERS user testing has centred on the engagement of a representative sample of archive users to interact with the demonstrator application and provide feedback on its strengths, weaknesses and potential for further development. The process of recruiting users involved advertising for volunteers via posters and flyers placed in various archive repositories across London as well as placing adverts in a number of newsletters aimed at archive users. The response rate was initially poor which led us to re-advertise offering participants the added incentive of a fixed fee for their participation. We also employed a more direct recruitment strategy by visiting the headquarters of a local society connected with archives and asking members to participate. These measures were successful and we were able to recruit a total of 18 users.

Back to top4.2 Profile of users

The aim in our recruitment of users to test the demonstrator was to gather a representative sample that would collectively reflect the characteristics of the archive user community as a whole

We recognised that a prerequisite for this approach would be to undertake an analysis of the types of people currently using archives. Without the foundation of preliminary research into the user market we would be in danger of ignoring or undervaluing particular user groups, and thus of introducing a bias into the results of our testing of the demonstrator

This realisation led us to conduct a preliminary survey of visitors to various archive repositories in the United Kingdom (full details of this will be published in the forthcoming "Understanding Users: A Prerequisite in the Design of New Technologies" in Journal of the Society of Archivists). The survey was conducted using a specially developed questionnaire based on a segmentation model developed by LEADERS to differentiate between types of archive users in accordance with three high level categories.

The first of these differentiated users according to "motivation for usage". The aim of this categorisation was to give us a broad understanding of why people are using archives in the first instance and what background they approach their research from, as a prerequisite for understanding their needs and behaviour. The sub-divisions used in this category were:

-

Professional/occupational users

Individuals engaging with archive material to fulfil an activity connected to their employment. Examples include users paid to undertake archive research; teachers; and academics affiliated with further or higher education institutions - Education/training users

Individuals using archive material to fulfil the requirements of a directed education or training programme. Examples include school students; undergraduates; postgraduates; and learners participating in adult education, continuing education or work related education programmes - Personal leisure users

Self-motivated individuals engaging with archive material to pursue their own interests - Personal obligation users

Individuals using archive material on behalf of another person - Other users

Individuals whose usage of archive material does not fit into any of the above

The second high level category differentiated users according to their primary research interest. This is important for LEADERS because knowing how users frame their own research offers a starting point in understanding how they might search and use archive material in an on-line environment. The sub-divisions used for primary interest were:

- Individuals, families or organisations

- Places including geographical locations and specific buildings/structures

- Topics

- Other

The third category differentiated users according to their perceived degree of familiarity with various aspects of archive research. This category required a self-assessment from users on their familiarity with their research interest, archive finding aids and documents, archive material on the internet, and the internet generally. Each of these is relevant to LEADERS because we felt that users' confidence and experience in these areas could influence their preferences for effective presentation of on-line archive material.

The results of the preliminary user survey were useful in giving us a broad understanding of the market for our products and providing us with the background data necessary to ensure that we could go on to engage a representative sample of users to give us detailed feedback on our work.

Potential participants in our testing of the demonstrator were asked to fill in the questionnaire used in the initial survey to ensure that we built up a sample that contained the same balance of types of archive users as we previously found to exist in the archive user community as a whole.

Inevitably, there are slight variations between our sample and the collective profile of the archive user community as revealed in our initial survey. We have highlighted these variations by giving the percentages of types of user found in our initial survey alongside those for our sample of 18 participants.

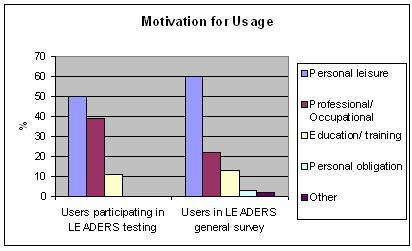

Motivation for usage

| Personal leisure | Professional/occupational | Education/training | Personal obligation | Other | |

| Number of users participating in LEADERS testing | 9 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Percentage of users participating in LEADERS testing | 50 | 39 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| Percentage of users in general LEADERS survey | 60 | 22 | 13 | 3 | 2 |

Table 1: Motivation for usage

Figure 1: Motivation for usage

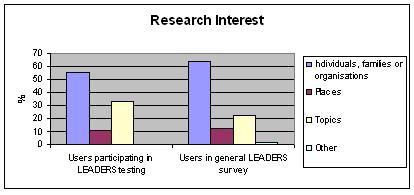

Research Interest

| Individuals, families or organisations | Places | Topics | Other | |

| Number of users participating in LEADERS testing | 10 | 2 | 6 | 0 |

| Percentage of users participating in LEADERS testing | 56 | 11 | 33 | 0 |

| Percentage of users in general LEADERS survey | 64 | 12 | 23 | 1 |

Table 2: Primary research interest

Figure 2: Primary research interest

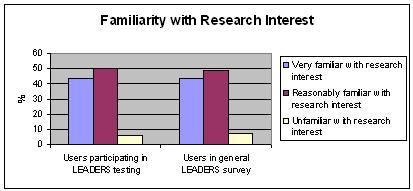

Familiarity with research interest

| Very familiar with research interest | Reasonably Familiar with research interest | Unfamiliar with research interest | |

| Number of users participating in LEADERS testing | 8 | 9 | 1 |

| Percentage of users participating in LEADERS testing | 44 | 50 | 6 |

| Percentage of users in general LEADERS survey | 44 | 49 | 7 |

Table 3: Familiarity with research interest

Figure 3: Familiarity with research interest

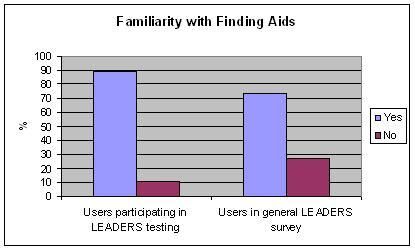

Familiarity with finding aids

| Yes | No | |

| Number of users participating in LEADERS testing | 16 | 2 |

| Percentage of users participating in LEADERS testing | 89 | 11 |

| Percentage of users in general LEADERS survey | 58 | 42 |

Table 4: Familiarity with finding aids

Figure 4: Familiarity with finding aids

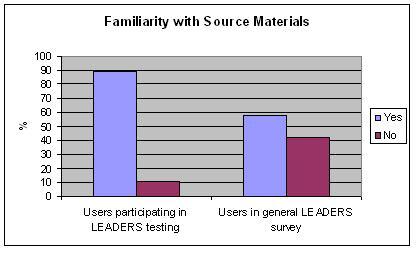

Familiarity with source materials

| Yes | No | |

| Number of users participating in LEADERS testing | 16 | 2 |

| Percentage of users participating in LEADERS testing | 89 | 11 |

| Percentage of users in general LEADERS survey | 58 | 42 |

Table 5: Familiarity with source materials

Figure 5: Familiarity with source materials

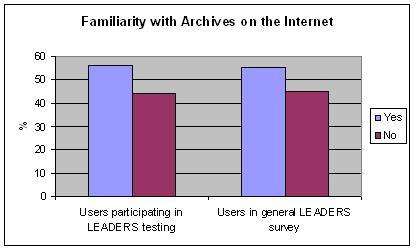

Familiarity with archives on the internet

| Yes | No | |

| Number of users participating in LEADERS testing | 10 | 8 |

| Percentage of users participating in LEADERS testing | 56 | 44 |

| Percentage of users in general LEADERS survey | 55 | 45 |

Table 6: Familiarity with archives on the internet

Figure 6: Familiarity with archives on the internet

This information on the types of users included in our sample is useful not just in relation to how representative the sample is of the archive community as a whole, but also as background that can help us understand why our sample responded to the demonstrator in certain ways. Where appropriate we have attempted to tie each user's response back to their profile to enable us to build up a picture of how different categories of users collectively responded to the demonstrator. In this report we have sought to highlight where there seemed to be consensus between users of a certain type and where there was clear differences of opinion.

Back to top4.3 Organisation of the testing sessions

The two testing sessions were held at University College London on 22nd October 2003 and 29th October 2003, with 9 users in each. An outline of the structure of the sessions is given below:

| TIME | ACTIVITY |

| 12.30-1 | LUNCH |

| 1-1.15 | Welcome and introduction |

| 1.15-1.45 | Overview of LEADERS demonstrator application |

| 1.45-2.15 | User interaction with the demonstrator |

| 2.15-2.30 | BREAK/REFRESHMENTS |

| 2.30-4.00 | Moderated focus group discussion |

Table 7: Structure of user testing sessions

Back to top4.4 Feedback from professional archivists

As well as understanding the importance of listening to users as part of the development of our tools and demonstrator, we also recognised the value of collating expert feedback on our research and development. This led us to set up a testing session with a group of professional archivists, which took place at UCL on 6 November 2003. When recruiting the participants we were looking to get a balance between archivists with advanced IT skills and experience of developing online archive applications and archivists without these specialised skills. Four archivists attended the session detailed below:

| TIME | ACTIVITY |

| 11-11.20 | Welcome and overview of LEADERS demonstrator application |

| 11.20-12.00 | Participant interaction with demonstrator |

| 12-1 | Moderated focus group discussion |

| 1 onwards | LUNCH |

| 2.15-2.30 | BREAK/REFRESHMENTS |

| 2.30-4.00 | Focus group discussion |

Table 8: Structure of testing session with archivists

Back to top4.5 Use of results in this report

The focus group discussions from all the testing sessions were audio-taped and transcribed to provide the raw qualitative data upon which the results are based. Although this report primarily makes use of the results from the two testing sessions with users, some information from the expert session with archivists has been included where their opinions differed from those of the users or introduced a different perspective on the utility of the demonstrator.

Back to top5. Results

5.1 Interface design

The users were asked to comment on the overall look and feel of the demonstrator. The general response was positive with the interface being described as " clear", "crisp", "simple" and "unobtrusive". This can be summarised by one user who remarked:

I think the fact that you are not particularly aware of it [the interface] is a good sign because you are concentrating on what you are looking at not on the design. It's when the design is a distraction that you have to worry, and your design isn't.

The users did make specific comments on the design and layout of certain screens within the application and these will be presented below under the relevant headings.

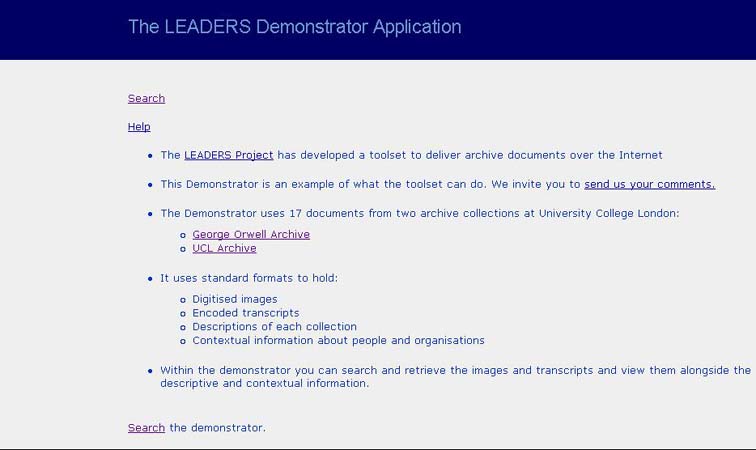

Back to top5.2 Welcome screen

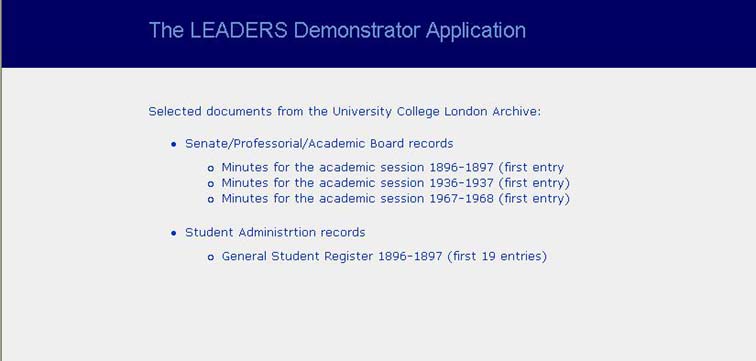

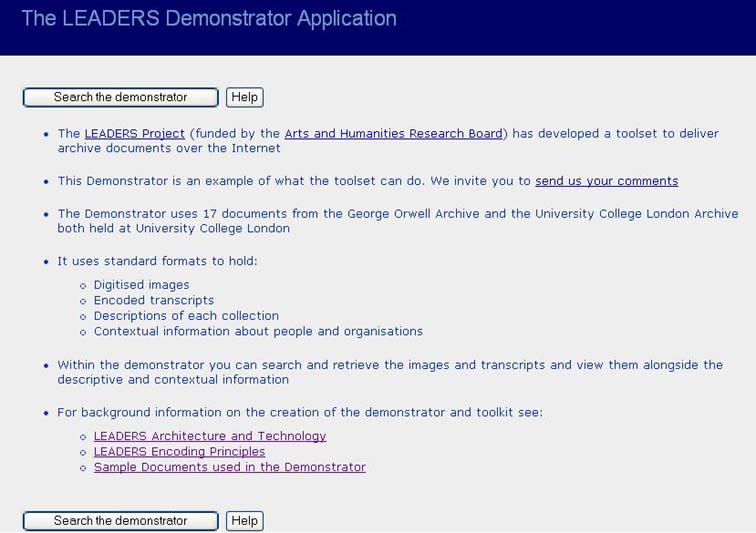

Figure 7 illustrates the welcome screen shown during the user testing.

Figure 7: Welcome screen shown to users

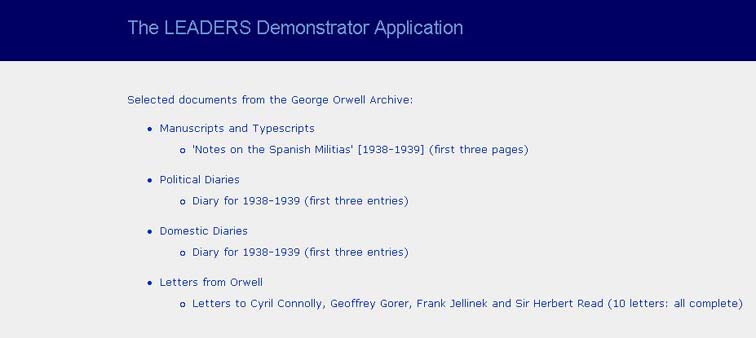

Figure 8: Screen giving further information on documents sampled from the Orwell Archive

Figure 9: Screen giving further information on documents sampled from the UCL Archive

The majority of comments made about this screen related to the links to the George Orwell Archive and the UCL Archive. These links took users to some further information on the documents sampled from each collection (see figures 8 and 9). Overwhelmingly the user's expressed an expectation that these would lead them not just to information about the sampled documents, but to the actual digital documents themselves:

It lead me to believe that because the front end has links [to George Orwell and UCL], that on clicking on the names of the prospective archives I would be portalled directly to documents from that archive

The disappointment and confusion that this misunderstanding caused can be illustrated in the comments of another user who remarked:

When I did click on the UCL archive, and got that screen up and tried to click on things on there ... I couldn't get to anything and then I didn't know what to do. I really didn't know where to go from there ... so if I was on my own I would struggle

There was also a general consensus that the links to the search screen at the top and bottom of the text were not prominent enough for the user to know that this was the navigation path they should take to retrieve the digital documents. One user suggested a solution to this problem:

Perhaps one way around this would be, instead of just having 'search' in the same format as the link to pages about the UCL Archive and the George Orwell Archive, make the search into a button so that it is clearly distinguishable

This feedback led us to redesign the welcome screen before the official launch of the demonstrator by removing the links to the George Orwell Archive and UCL Archive and transforming the link to the search into a button (see figure 10).

Figure 10: Modified welcome screen

Back to top5.3 Search screen

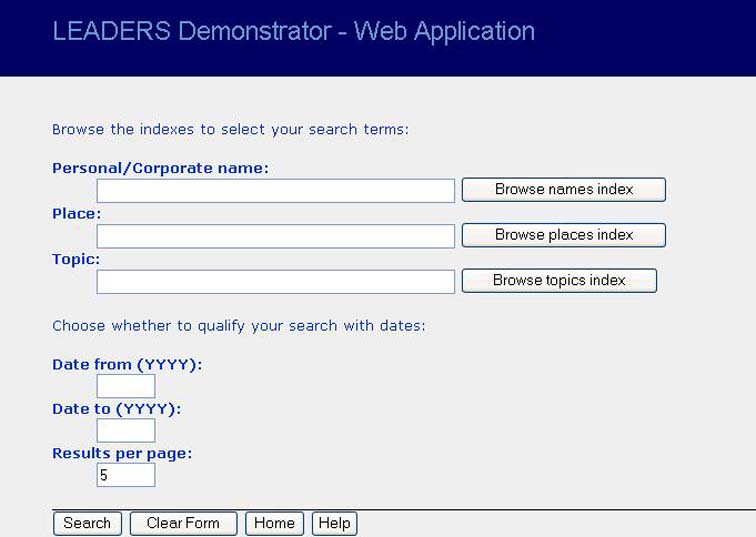

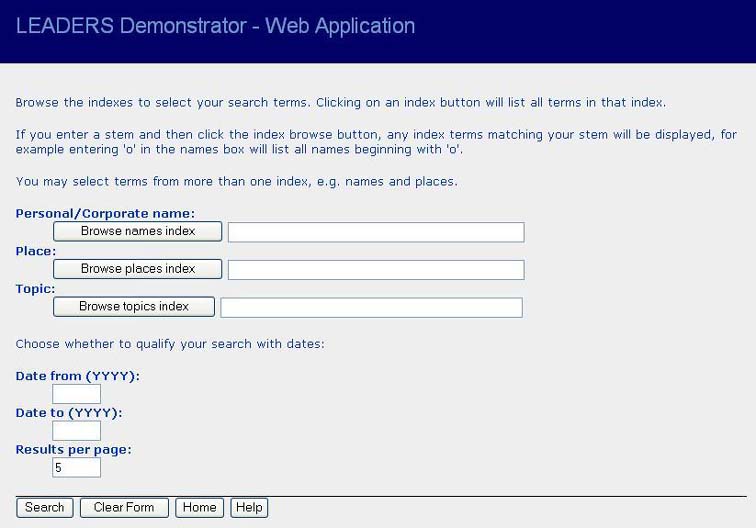

Figure 11: Search screen shown to users

Figure 11 illustrates the search screen shown during the testing. Several users expressed initial confusion as to the nature of the search that the form would allow them to conduct. This confusion seemed to stem from the inclusion of open text fields on the form:

What I don't understand is, you have to use the browse button to search the indexes so what is the point of having the text field?

It became clear that some users associated the open text field with free text searching and believed that it was there to enable them to enter word/s of their choice. In reality, the open text fields are only included to enable the input of the stem of a word before browsing the index. Entering a stem before hitting the browse button will take the user to the nearest corresponding place in the alphabetical list of terms:

Moderator: Did you find this screen which allows you to pick your search terms from the index easy to use?

User: I had several attempts before I found anything ... I eventually got the hang of it though and managed to work out what I was supposed to do. I was putting a corporate name in and then clicking on the search and I was coming up with no hits. Especially when I kept putting UCL in and it didn't want to know UCL ... I had to sit down and think very carefully about what I wanted to try ... I eventually worked out that it is down as University College London in the index not UCL ... and I had to use the index to enter the term.

These comments led us to change the design of the form in two ways before the launch of the demonstrator (see figure 12):

1. We added some more explanatory text at the top of the form to explain how a search can be formulated

2. We moved the position of the browse buttons so that they appear before the open text fields to make them more dominant

Figure 12: Modified search screen

The comments we received illustrate the importance of understanding the assumptions that users have when faced with particular layouts of search forms and the importance of choosing designs that won't contradict preconceived notions and past experiences. With more time to invest in the design of the form we would explore possible mechanisms for a closer integration between the open text field for inputting stems of words and the index terms so that the relationship between the two is clear. One user suggested a possible mechanism for this:

If you do stick to index only searching then it would be quite good to have a drop down box that appears as you type in your stem which shows the relevant index terms in relation to what you are typing

In the design of the demonstrator shown to the users, further explanation on how to search was available via a help button on the form. However, the users who were struggling did not click on help but rather continued to experiment with the form adopting a trial and error approach to learning how to retrieve the material they were looking for. Our users were not prepared to take their focus off the main screen to look for guidance on how to use the application. This suggests that caution should be applied when providing separate help pages. Explanatory information should be alongside the relevant screens or parts of the screen wherever possible.

Back to top5.4 Searching via indexes

The response to searching via pre-defined index terms was varied. On the positive side, several users commented on the usefulness of having the terms divided into names, places and topics:

I think it is useful to be able to search via the indexes, especially divided into name, place and topic like that. There are words that could be a name, or place or topic. For example, 'Brown' could be a name, or it could be a place like Brown Street or it could be a topic because it is a colour, so having the indexes likes this allows you to choose the right one more easily

There was also agreement that the indexes had the potential to help people who did not have a clear idea on what they want to search for with the potential to act as a guide to the contents of the sources:

Sometimes if people don't know what they are looking for but they are generally interested in George Orwell then they might look down at your topics as a guide to what they should search on. So the indexes could inspire them to decide what they want to look at

However, users who fell into the categories of professional/occupational and educational/training, especially those who came from academic backgrounds, expressed a fundamental dislike of indexing:

My principal difficulty with this whole approach is that this is another set of minds interposed between me and the documents

The majority of the academic users commented on how they believed the indexes were forcing them to access the material through the preconceived categories imposed by the indexer who they instinctively do not trust:

I don't like the indexing ... I don't like the idea that somebody is imposing their presuppositions on the documents. If you had the archival hierarchy that you could explore at its broadest and at its most detailed and if you combine that with a free-text search you could squeeze the index out altogether

Regardless of whether the users liked or disliked using pre-defined indexes for searching, there was general consensus that more explanation was needed on the process and methodology employed when formulating the indexes to aid the users in their assessment of the validity of the chosen search terms:

Can I ask you what your criteria was for choosing what went into the indexes and what didn't ... I tried several place names that were in the document but didn't appear in the index. All I am saying is that if there is a selection process going on then I want to know about it because otherwise I am thinking this doesn't work for me and I give up and go and try something else

Back to top5.5 Desirable search functionality

In discussing desirable options for search and retrieval that move beyond what is currently offered by the LEADERS demonstrator, it became clear that there was a separation in viewpoints between those who were familiar with using archival material on the internet and those who were not.

The users who were unfamiliar with archives on the internet were less keen on being presented with multiple search and retrieval functions commenting on the importance of simplicity in any functionality offered:

Everyone has to start somewhere, and when they do, even if they are just new to computers, they just don't know what to do, so the simpler the better. They want to be able to click and know that they are going to get to something quickly.

The majority of those who categorised themselves as novice on-line archive users stressed that if different search options are offered in an application, then a clear route from the simple to the advanced needs to be provided:

My friend over here has obviously played with modern computer software a lot more than I have and knows what he is doing but a lot of us don't so we need simplicity. We may learn from those simple starts and progress to a more advanced stage and want lots of different options but we need to start with something simple and very easy to use to give us confidence. Otherwise you just pull the plug, because you think to hell with this I don't want to play this game anymore

There was a general consensus across all the users, whether novice or expert, that they would like to have been offered the option of searching within one archive collection at a time. This option may be even more desirable in a larger application with data from a high number of collections as a means of narrowing down the number of hits returned:

Not being able to search in one collection at a time [is the demonstrator's main weakness]. In other words via your way of searching if you bring up a name you have no idea if it is connected to the George Orwell Archive or the UCL Archive.

Users were asked to comment on whether they would like to be provided with the option of browsing the finding aids to reach the digital documents. Within the LEADERS demonstrator, selected finding aid information is provided alongside the digital documents as a means of setting the transcripts and images in context. However the finding aids are not accessible in their entirety and cannot be used as a means of navigating to the digital documents. Users differed in their response to this possibility. Here it seemed that the user's background motivation for using archival material affected their responses. The professional/occupational and education training users who came from an academic background particularly stressed the importance of having such an option:

What the user would like, or at least what I would like, is some form of familiarity with the archive collection's hierarchy so that you get a feeling of what sort of records you are going to be looking at before you actually view the documents. You want to be ahead on the sort of information that you are looking for, and what you will do with it when you have found it. You want to know where the document sits in the hierarchy of the collection. How useful is it going to be? Are there any other documents like it? How is its utility affected by how it was produced? You need to be able to move in the description of the archive collection as a prerequisite

Here, the academic users (who were also familiar with archive finding aids and using archives on the internet) referred back to their surprise that the links off the home page did not lead to such a facility:

I would like a browse function. This goes back to the discussion about wanting links coming off the information pages about the George Orwell Archive and the UCL Archive. The ability to browse could be associated with those pages or associated with the search option.

However, in contrast to this various personal interest users (some of whom were also novices at using finding aids and archives on the internet) expressed concern that such an approach would leave them in a state of confusion:

I like it the way it is. I wouldn't have actually gone any further if I had been confronted with some hierarchy it would have been far too confusing. The way this is designed is simple and user-friendly. It gives the right information at the right time.

It is important to stress that for such users, the provision of contextual information from the finding aids alongside the documents within the demonstrator was an important and useful feature. These users were interested in gaining an appreciation of the provenance of the material contained within the demonstrator as well as an understanding of the relationships between the items. They also recognised the utility of descriptive information relating to the creation, acquisition and administration of the originals from which the digital documents are derived. Therefore, their ambivalence to the provision of a 'browse facility' based on finding aids was not due to a lack of interest in the information that finding aids contain but rather related to concern that browsing through hierarchies of description would be a complex and arduous task.

The academic users commented that they did not believe that a 'browse facility' should be the only option available:

It is true that if you have a very clear idea on what you are looking for then you can waste an awful lot of time if you are forced to go through general categories. Scrolling down through the layers of description can get frustrating ... I wouldn't want to be forced to go in that way but it is a useful and important option

The users were asked whether they would like to have had a 'free text' search option which would allow them to enter terms of their choice which would be matched against the full text of the transcriptions. The response to this question was more muted than expected. The majority agreed that this could be useful but nobody expressed any strong viewpoints either for or against this functionality.

A similar response came when the users were asked whether they would like to be able to search via basic descriptive information about the documents such as title, author, date of creation or reference code. However, this may be because this function would be particularly useful when returning to the application as a means of quickly retrieving a document that has been looked at previously. As the users only had one session with the demonstrator and were using it under 'false' circumstances (not in real research) the utility of such functionality may not have been apparent.

The participants in both sessions were also asked to comment on the usefulness of being able to conduct Boolean searches, having options for wild carding, and other advanced search functions. Here the academic users reinforced the notion that the more options and functions presented to them the better. The majority of the other users remained silent on this issue.

One personal interest user suggested that they would like to be able to conduct searches across the biographical information contained within the EAC authority records:

User: Is it possible to go straight to biographical information on people rather than just getting a list of documents?

Moderator: It's not, but would you like that feature?

User: Well just as a casual user if you were interested in the George Orwell Archive but you didn't know much about it you might want to read about George Orwell immediately. I know it is fairly easy to find because it comes up alongside the documents but some people may want to do some background reading before looking at individual documents

This is particularly interesting because it challenges our initial assumptions about the purpose and utility of the contextual information within the demonstrator. We designed our search and retrieval around a notion that the user will always be looking to retrieve the digital representations of the archive documents. We did not consider the possibility that searching on and for the finding aids and authority records may remain a necessary requirement in systems that contain versions of the documents themselves.

Our findings leave implementers of generic applications designed to appeal to all archive users with a difficult balance in catering for those who want multiple search and retrieval functions with users who express concern that being confronted with advanced search functionality and multiple search options would leave them confused and disorientated. This issue is summarised by one personal interest user who categorised himself as a novice at using archives on the internet:

I think it very much depends on how the search options are presented. There is a great danger that if you present too much at once and too many fancy features then people like me are going to get totally lost ... on the other hand there are people like my friend over here that need to be offered multiple search options.

Back to top5.6 Search results

Figure 13: Example search results screen

Figure 13 illustrates an example of the search results screen within the demonstrator. There was some debate between the users as to whether there was enough information given about each hit to enable the user to decide whether to click into the detailed displays. One personal interest user commented:

Before you get to the transcript and images I would like more information telling me what I am going to view, I would like more of a preface so I can decide whether to view that document or not.

Other users refuted this suggestion, commenting that in an on-line environment when the actual document is only a click away, detailed scope and content information isn't necessary as a prerequisite to viewing:

The fact that your search had thrown them up was enough for me, if the description was even less detailed that would be fine. I suppose in the past you would have looked at handlists and deciding what to order was a big decision because it would take ages for the staff to retrieve the actual documents. Therefore the more detailed the initial description the better to avoid calling up the wrong thing and wasting time. Here you can do a search and with one click you have the document. If it's the wrong document, with one click you can come out of it and look at another one, so a detailed description prior to viewing isn't so vital

The users acknowledged that the level of detail necessary on this screen may vary according to the length of the document being described. Where the document is a short letter, only a brief description of its scope may be necessary as the user can click straight into the transcript and read it through quickly to gauge its contents. However, where the document is a minute book, with multiple entries running over 100s of pages, a more detailed summary of its content may be useful to save the user having to trawl through the actual document to surmise its utility:

It also depends on the document that is being described. If you have transcribed a massive minute book, then a good summary of its contents on the search results is going to be useful because it will take you ages to gauge its usefulness from scrolling through the transcript. With a letter you can read the transcript in five minutes so a prior detailed description on the search results page isn't really necessary

The search results in the demonstrator are ordered alphabetically and are presented over several results pages. Although the users we engaged with were happy with the order and presentation, our focus group with Archivists highlighted some important design considerations in this area:

Archivist 1: When you have only got 10 hits then grouping it like this is fine because you can easily decide what to do next but when you have got 300 hits ...

Archivist 2: With a larger data set having options to sort by is useful so letting the user sort their hits by date, frequency of number of hits or by keyword would be important ... [Also] some kind of preliminary grouping of hits might be needed as a starting point because there would be so many that they would be unmanageable.

These comments highlight the fact that the design of useful results pages will vary depending on the volume of data being dealt with. In large applications where there will be larger numbers of hits returned as a result of any search, the ordering and presentation becomes more of an issue, and options that allow the user to sort their hits in different ways and even some kind of conceptual grouping of hits in the first instance, may become important design features.

Back to top5.7 Detailed displays

General Issues

Link between search terms and their relationship with the document

A recurring comment about the detailed displays that was made forcefully both in the user sessions and the focus group with archivists was the need for a link between the chosen search terms and the parts of the document relating to those terms:

User: I would like a different sort of highlighting. When you have searched on something, say a name, it would be extremely useful to have that name then highlighted in the transcript so you can find it quickly. I've seen it done before.

Moderator: Yes that is a very good point. So it would be useful to have a link between what you have searched on and its position in the document. So the name that you have searched on is highlighted?

User: Yes in yellow or something, whatever makes it stand out from the rest. You just cast your eye down. So you can see how central that person is within the document and assess the usefulness of the document quickly. For example I was looking for Professor Gower and the minutes came up and I had to look for ages within the document to actually find him

there is an issue with linking search terms to where they appear in the document, particularly in relation to topics, as there is no guarantee that the word chosen as the index term will be present within the actual text. Making such a link would undoubtedly be easier in a search environment where a free text approach is taken where the search terms entered are matched against the full text of the document. Nevertheless, there was an overwhelming consensus across the users and archivists, that providing this functionality is a vital requirement.

The default view

Within the demonstrator, when a user enters the detailed displays of the transcripts and images for their selected item, the 'transcript with context' view is presented first as the default. The users were satisfied with this choice of a default view, but in our focus group with archivists this prompted detailed discussion. One archivist in particular felt strongly that the users would favour seeing images over transcripts, and therefore images of the item should be the default:

My initial thought was that it should be the image that you see first rather than the transcript but then with the option of seeing the transcript ... The feedback that we have had from users is that they want to see images of archives. So give it to them as the first thing

Another archivist in this group, argued against this viewpoint by suggesting that the transcript should be the default, especially in an application developed to include the added functionality of a link between the user's search term/s and their position in the document, as such a link would inevitably be made within the transcript:

But when I reach this from the search the first thing I want is to be able to scroll down the transcript and see where my search terms appear in it. You couldn't do that with the image. So I want the transcript and then the image.

This led the archivists to suggest that perhaps the ideal solution was to let the user decide which view they want to access in the first instance by giving them the options on the search results screen:

Archivist 1: Or even on the results page give them the option there to view image or view transcript so at that point they can click on the view they want

Archivist 2: Yes that would be ideal

Ability to minimise parts of the screen

The other general issue that the majority of the users agreed on was the addition of functionality that would enable the user to control parts of the screen by minimising it and bringing it back up when required. These comments were made mainly in relation to the contextual information and metadata that appears in the right hand frames across the views. The general consensus was that having the information appear in the right hand frame in the first instance was useful, but that at times, particularly if they were working on an item for a long period, they would like the option to minimise the right hand frame and focus only on the contents of the left hand frame.

User 1: You may want to minimise the right-hand frame and work just on the transcript

Moderator: Can I just pick up on that. I get the sense that you think there are bits of information that are useful to see but you would like to have the ability to just focus on one bit completely at any one particular time. Rather than having them all always available. Is this a good starting point though, or do you want to start with the transcript in full with links to other things?

User 1: Oh no, this is useful. You need to see everything and then have the option of minimising bits of it.

Moderator: So this screen should act as a super sampling menu?

User 1: Yes

User 2: Yes I agree, you want to be able to minimise and enlarge as you choose

User 1: Yes I would have liked to be able to minimise bits of the screen and bring them back when I needed them

In the focus group with archivists there was the same agreement that it would be useful to be able to focus in on just the transcript or images, but the solution offered differed. Where the users wanted the information presented all on one screen in the first instance, with added options for minimising parts of the screen as required, the archivists felt that having it all on one screen was too cluttered and busy to be useful and suggested that the transcript and image should be given more of the screen with links leading to the contextual information and metadata:

Archivist: I still think they should see the image first of all, and then if they want to go down to the transcript and other levels of information.

Moderator: Would you put anything alongside the image then?

Archivist: Just options to look at other stuff. Links to everything else would make it a cleaner display. It might be easier without the frames.

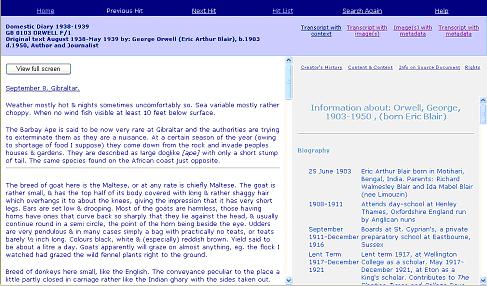

Transcript with context view

Figure 14: " Example transcript with context view"

Usefulness of the encoded transcript

When asked whether having a transcript of the archive document is useful (see figure 14), the overwhelming response was positive. The users were able to see the potential of the transcript to solve the kinds of legibility issues often apparent when using archival material:

Yes for me I was thrilled [with the transcript], because when I was studying for my masters and using the archive regularly there was a real issue with legibility. I came across one whole minute book that I couldn't read. I still have no idea what is in that minute book, it could change everything, but I don't know! So having it in the form of a transcript would be fantastic.

The majority also commented on how having the transcript could save them time in the overall research process:

I have just had the experience of looking at some eighteenth century wills and I haven't finished dealing with them because I can't spare the time to transcribe them. If you are experienced in reading hand-writing then ok may be you aren't going to be so bowled over by this demonstrator but for me who isn't experienced. I can spend a whole day trying to decipher one word so I can't say how valuable this is to someone in my position. If someone else is prepared to invest the effort in the first place then that saves no end of time and sweat for us. You may question whether the transcriber has got it right. That is a whole different ball game but at least somebody has had a go.

Interestingly, some of the academic users questioned whether all archival material is suitable for transcription:

User: Well with the student register it is legitimate to ask who is going to use that data set, and given who is likely to use it, wouldn't it have been just as good to have one of the forms digitised or as a facsimile and index the rest of the information in a database?

Moderator: So you are questioning the usefulness of the transcript in certain cases?

User: Yes it is a very heavy handed way of achieving the result.

There is no question that transcribing archive documents is a time consuming and costly process, and because of the investment needed, it is important to question whether other less labour intensive methods of providing access to the content are more suitable. The added value gained from producing an encoded transcription of a document relate to having a legible representation of the original, the full text of which can then be searched. The encoding enables different views of the original to be created with varying degrees of editorial intervention imposed on the document, and allows contextual and interpretive information to be linked into the flow of the document. It is possible to argue that these gains are most applicable to archive material that is likely to be studied and used as 'text' rather than just as a source of data, as one personal interest user suggested:

Well I am not a genealogist and I just wonder if a lot of the people here are coming from the prejudice of how they have used the internet before in their research ... I am interested in George Orwell as a person, a subject if you like, his archive to me, isn't about searching through lists of names, so perhaps people are finding it difficult to relate their prior experiences to the material in the demonstrator. For me, having looked at the way material is presented on the Internet before, and with my interest in exploring text as 'text' I found this a really helpful way of looking at somebody's writing. For someone with my interest who wants to study the words rather than just look for a name this is ideal.

This report has touched on the possibility that different types of users may be looking for different search and retrieval functionality within an archive application, and perhaps we can question whether the whole concept of the provision of transcripts of archive documents is more useful for certain types of users than others. Does a user's motivation for using the archive have any bearing on this? Do professional and educational users, especially those with an academic background, gain more from the provision of digital representations of archive documents, than say, personal interest users? Or is it connected not to motivation behind the research but to the purpose of the research? Do users interested in researching topics gain more from this kind of application than say, users interested in researching individuals or families?

Our research reveals that in actual fact all users can potentially gain from accessing transcripts of archive documents, regardless of their motivation or purpose. This is borne out by the fact that the users who spoke out positively about the transcript were varied and were representative of a broad mix of motivation and purpose for using archival material.

So the key to understanding the appropriateness of providing access to archive material in this way, is not connected to the type of user accessing the material, but to an understanding of whether the archive material can be classed as being predominately 'data' or 'text' based. Differentiating between types of archival material in this way is the key to understanding whether encoded transcription is an appropriate method of presenting and delivering the document to the user in an electronic environment.

Data orientated archive material is most usually found in administrative archive collections and includes document types such as census returns, parish registers, ledgers, account books and forms. Such material is often structured in a way that allows the data contained within the document to be meaningfully sampled, normalised and transferred into a different structure designed to capture electronic data, for example, a database. In such cases, the provision of user access to the data within the document is of primary importance, and if the meaning of the data can be maintained after the transferral process is complete, then we must ask whether there is any point in choosing encoded transcription as an alternative method of delivery. Certainly a drawback in using a database to store the information, is that the connection between the data and its presentation within the original source is lost and some of the subtleties of meaning conveyed in the positioning or structuring of the information may be overlooked. Some users may be interested in the way that such documents are structured and positioned in order to draw out such subtleties and in their case they will need as close a representation of the original as can be achieved when delivering previously hard copy documents in an electronic environment. Although encoded transcription is likely to offer a closer match between the original source and the derived digital output, it is important to stress that the use of encoded transcription as a technique does not necessarily lead to a literal representation of the structure, format and layout of the original due to the complexities of representing such features through the encoding. Therefore, it is legitimate to suggest that with 'data orientated' material, careful thought needs to be given as to whether producing encoding transcripts is the best technique.

However, encoded transcription is a more suitable choice for archive material that is predominantly textual in nature. Such material includes documents structured predominantly as prose and includes letters, diaries, memos and essays. Within such material the information, facts and meaning within the document is inextricably entangled within the flow of the text making meaningful sampling, normalisation and transferral to the highly structured format of a database record, a difficult if not impossible task. In such cases, encoded transcription allows the material to be presented in the same flow as the original with the encoding allowing for the search, retrieval and manipulation of the document as required.

Our results indicate that there is no direct correlation between a user's motivation and purpose for using archive material and whether they are likely to be more interested in data or textual resources. Educational users interested in a topic are sometimes interested in fact finding via data resources and sometimes interested in viewing textual material. Equally, personal interest users researching individuals and families are sometimes merely looking for the presence of a name in a data resource and sometimes interested in texts related to the individual they are researching. It is also important to note, that it is possible to use textual material as a data resource, and sometimes a user will be looking merely for data within a text-based document. The difference between archive material that is data orientated as opposed to textual is often a grey area with some archive material overlapping between the two. However, we would argue that it is through an understanding of 'types' of archive material that the clearest assessment of the utility of providing transcripts can be made.

Relationship between the transcription and the original

The professional/occupational and educational/training users who participated in the focus groups were particularly concerned that the transcription of the document should be as close to the original as possible, with minimal editorial intervention. They expressed the view that the integrity and validity of the transcript was dependent on this factor:

User 1: I am worried that if you have corrected it then it isn't the original. I want the transcription to be a word for word copy of the original. It's only useful and valid to me if it represents the original.

User 2: There is one addition in that letter where I think you have made the wrong correction. The word 'he' shouldn't have been inserted. It's a trivial point but it illustrates the fact that those of us reading it may not concur with the corrections.

User 3: Yes may be it is better if it is exactly as it has been written

Moderator: So you would rather have something with no ...

User 1: It worries me that you would consider not taking a literal representation of the original

User 4: Yes transcribing it is one thing editing it is another

This debate prompted discussion between the users, some of whom recognised that there are times when editorial intervention can help to give the document meaning and can aid the flow of the text making it easier to digest and read. The moderator suggested the following solution to these issues of literal verses editorial versions of the document:

Moderator: Well I think what we could do here is have different versions of the transcript. You could have one where there are additions and corrections, an edited version of you like, and one where it is a literal transcription. So you could have different versions that you could work on depending on your preferences. Would that be good?

The users responded positively to this idea. It is worth highlighting the ease in which this could be achieved within a LEADERS application. As the transcriptions are encoded, multiple versions of text can be produced from the same document through the use of stylesheets.

Dealing with presenting long documents as transcriptions

The users commented on the fact that all the documents within the demonstrator are relatively short, and questioned how longer archive documents would be presented within the application:

What I don't get a feel for is how this would work on a very long document that is in itself a complete piece. How would you treat that? Would you split it up? Navigating inside a long document and jumping from one bit to another is a challenge

Certainly any implementer intending to create their own application based on long archive documents would need to think carefully about how these would need to be presented to the user in a way that makes them easy to navigate within the confines of the application.

Functionality within the transcript

Due to the fact that the transcriptions are encoded, there are a number of special features available which the users were asked to comment on. The first of these is the provision of biographical and administrative information linked to names that appear within the flow of the text. This functionality received an overwhelming positive response:

I think it is really useful. Certainly for students just starting on a topic they are not going to know everything about it so being able to read some background as you go through a document is really useful

The transcripts also contain various highlighting and tooltips within the flow of the document which attempt to draw attention to and provide information on aspects of the transcription or editing of the text. For example, if a word was deleted by the creator in the original and replaced with another word, the deleted word appears crossed out in green with a tooltip that tells the user that the deletion was made by the creator. Similarly if a word has been added to the text by the encoder as an editorial intervention, it is highlighted in red with a tooltip to indicate responsibility. Bearing in mind the positive response to the possible provision of different versions of the transcript both literal and edited, the users thought the inclusion of highlighting and tooltips was potentially useful but that more explanatory information was needed within the demonstrator to support these features. Several users suggested the inclusion of a key so they could understand what types of textual features are highlighted and why:

User 1: The information on the right hand side didn't give you any clue about why some of the text was in different colours. It didn't tell you

User 2: You could have the information in a key to download somewhere so that we can print it off and have it to hand as a reference when we are looking at the transcript

User 1: Or have it in the help files because there wasn't any explanatory information about it there

User 3: I don't understand the ones in red. It just said correction. Does that mean you have changed it?

The users were also asked to suggest other useful functionality that could be included with the transcript. Several personal interest users suggested having more interpretive information linked to words or phrases within the text:

User 1: Something like that could be useful for other things too. If anybody has used old inventories or any old writing in fact, when the word is something that you don't understand, if you highlight it and can get a description. That would be fantastic

Moderator: So like dictionary definitions or a glossary linked to certain words?

User 1: Yes, there are so many possibilities

User 2: Words that aren't used in modern English need explaining

User 1: Sometimes even relationships in wills, for instance, someone might say, 'my brother German' which means 'my full brother' not a 'half brother'

Interestingly, one academic user questioned the appropriateness of providing too much interpretive information by responding to the personal interest user's suggestions with the following remarks:

User 1 (academic): But that is interpretation, that is the trouble with that

User 2 (personal interest): What's wrong with interpretation? As long as the person doing it knows. It might be helpful.

User 1 (academic): Well you have to be very sure of your ground

This is indicative of different levels of interpretation and added contextual information being necessary for different types of user. In general, our research seems to indicate that such additions within the transcript may be more appropriate for personal interest and educational users than for professional users, especially those with academic backgrounds. Overall, the professional users were less interested in such features and more likely to question the validity of anything that is provided.

Contextual information in right hand frame

The response to the contextual information provided in the right hand frame of the 'transcript and context' view (see figure 9) was overwhelmingly positive and can be summed up by the following remarks:

User 1: I think the very detailed contextual information [in the right hand frame] is excellent it all makes it very valuable. You are not seeing the document in isolation but are getting all of the information that surrounds it and makes it intelligible. It's such a great teaching tool

User 2: The level of detail of it all is just fantastic; everything you need to know is provided for you so you gain an appreciation of the document and the collection it comes from very quickly and easily

User 3: Its got so much information available in the one place. Everything is there that you should need. It's all there.

However, in relation to the 'content and context' view, the users came up with several suggestions for improvement. In this view, scope and content information from all the levels of the finding aid are presented via a bottom-up approach, starting with the scope and content for the corresponding transcribed item and moving through the levels of description to the scope and content of the whole collection from which the item is derived.

Firstly, the users suggested that having the information presented to them in this way offered a tantalising glimpse of what other material was available within the collection in question, and that the application would be enhanced if links could be made to the other items listed:

Once I was on a particular document, say a diary, then from the content and context view I would have liked to have got to the other material that it tells me is available but there didn't seem to be an obvious way of doing it. I liked the stuff on the right hand side because you could see how it was using all the bits of archival description very cleverly to place it in context but it would be nice to be able to step out and back again.

Secondly, the users questioned the use of terminology on this screen suggesting that 'fonds' and 'sub fonds' were not useful ways of describing parts of the collection.

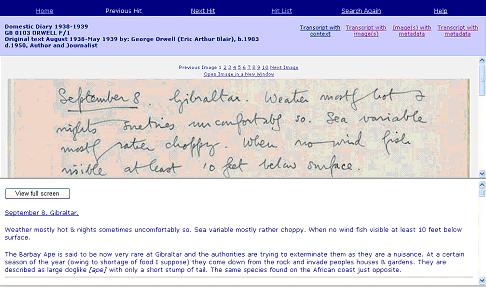

Transcript with image view

Figure 15: Example transcript with image view

The transcript with image view (see figure 15) received an extremely positive response. The users remarked that by having both the image and transcript presented in this way was ideal. The transcript had potential to help them decipher the original and the image helped them to check the accuracy of the transcript:

User 1: Sometimes when you are looking at a transcript you think 'I wonder if what they really mean is ... ' well with this you can ... look at the image and check the validity of the transcription. The transcriber may have been slightly less familiar with the material and they may have mis-spelt something ... well with this you can check.

Moderator: So you feel that having the image can verify the transcript?

User 1: Yes, and this is the problem when things are put on the Internet without the image. You are constantly questioning ... here you can go directly to the image and think 'yes that is right ' or 'no that is wrong' and you can see why the mistake has been made.

User 2: I am working on sixteenth and seventeenth century documents so to be able to see them both on the screen together at the same time is great

However, several participants commented that the utility of this view would be enhanced if the transcript and images could be made to work more intelligently together, so that when a particular part of the transcript is viewed the corresponding image is automatically displayed and visa versa:

When you change the image you have to scroll to get the transcript to match the image and I wondered whether it was possible to have it so that when you changed the image the transcript automatically jumps down to the right place

Due to the encoding within the transcript it would be relatively straightforward to match the images and transcript on a page by page basis via a manipulation of the encoded page breaks. It is clear that this added functionality would greatly improve the usability of this view.

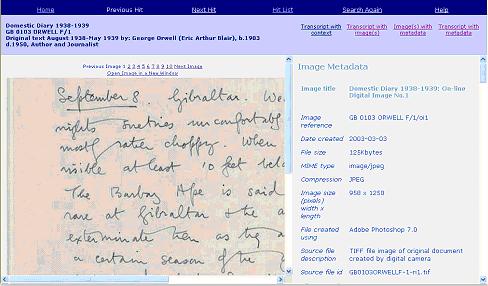

Image with metadata and transcript with metadata views

Figure 17: Example image with metadata view

Figure 18: Example transcript with metadata view

The general response to these two views (see figures 17 and 18) was more muted than the response to the previous detailed displays. The general consensus was that it was reassuring that the information has been captured and recorded, but that it is too technical to be of general use and should therefore not be given such prominence within the application:

User 1: I am glad it is there. It doesn't interest me, I am not that technical but there must be ... people who are. When you talk about the TEI or whatever, it goes right over my head but I appreciate that there are people who care about this other language

Moderator: But none of those people are in this room! It is interesting because you are all saying yes other people will find it useful, but in fact there isn't anybody who fits in to that category present here

User 2: That stuff is for what I would call advanced researchers not for people like us

User 3: It might be useful to someone but you don't want it continually on half the screen

The users suggested having a link to this information for the 'specialist users that might be interested' without allowing it to take up half of the screen on two views. The exception to these comments came in relation to the information contained half way down the right hand frame of the 'transcript with metadata' view under the heading 'encoding description'. This information provides some guidance on the editorial intervention imposed on the transcription and the users suggested that this information is important but its relative positioning was unhelpful:

User 1: Well the order that you have it in isn't helpful because the file size doesn't interest me in the slightest but the encoding description down the bottom does

User 2: It must be very difficult for you to make judgments like that. I think the problem is that the interesting bit is somewhat hidden

User 1: Yes as it is we didn't know where to look for that information so that needed to be more immediate

Clearly, there are some re-design issues centring around these two views. In particular, there is a need to reduce the prominence of the more technically orientated metadata whilst still making it available somewhere within the detailed displays. There is also a question over what information currently concealed within this metadata is of more general use and wider appeal, and how this information could be repositioned to make its availability more obvious.

Back to top5.8 General comments

The importance of access to original material

The users were keen to stress that viewing digital representations of archive documents could never completely replace the experience of seeing the originals:

User 1: There is still something about seeing and touching the original even though you get smelly and dirty and covered in all sorts there is still something about looking at the original

User 2: Yes you don't get the same thrill from a JPEG do you? But at least you get to see it

Several participants also highlighted practical reasons why access to original material is necessary in certain cases:

User 1: I was looking at something at Kew1 the other week and I had seen a transcript of the document but then looking at the original I noticed the paper was torn and the surname had been ripped off. So the transcript had the second first name down as the surname but it was just the middle Christian name. In that case it was vital for me to see the original.

User 2: Well with the quality of the images in the demonstrator, they are good enough when enlarged to the full screen that you could actually see where George Orwell's letters had been folded. So there is quite a lot that you can pick up from the images if you look closely. Having the image allows you to make the decision, yes that is the document that I really want to go and have a look at because there is something there that doesn't look quite right and I need to check it out

A recurring theme within the focus groups related to a concern that in the long term, the delivery of digital representations of archive documents might further restrict user access to original material:

What I worry about in all of this is when stuff gets digitised and transcribed and it's on the Internet that it will become harder to see the originals

It is quite clear that the user community need reassurance that physical visits to an archive repository to access and use original archive material is still recognised as an important and vital aspect of archive services.

Concerns over lack of resources in the archive sector

Interestingly, the users were also extremely aware of issues relating to lack of resources in the archive sector. Their responses to questions were occasionally limited by disbelief that anything of this nature could realistically be achieved in practice with current staffing and funding levels within the sector at large. In response to one user's request for glossary definitions linked into words that appear in the transcript another user heatedly remarked:

User 1: Well I think you are all talking about an impossible ideal world because to get all these things transcribed to start off with is a massive task, if you then ask for explanations of words, which quite frankly anyone who is interested in research should be able to look up in a dictionary ... how long is that going to take?

User 2: Yes but this is what computers are for, to save us time

User 1: Nonsense, nonsense, you have to think of the time it will take. People ask too much, and if we ask too much we will never get anything. Give me the transcription and leave it to me to find out the extras. I can use books. Otherwise I shan't live long enough to see these things done.

One professional user with an academic background raised a deep concern that the impossibility of transcribing and imaging whole archive collections would lead to sampling from archive collections and this would compromise the utility of the digitised material:

User: On the whole if I can strike a note of discord I can only see certain circumstances in which this [application] would be a very good research tool. Unless you are saying you are going to put a whole collection up in its entirety which there just isn't the resources to do.

Moderator: Well what if we did put a whole collection up?

User: Well then yes that would be excellent. It would then be an unrivalled research tool, but I just don't think that in practice that is going to happen, so I think on the whole its not likely to be a very viable tool for academic research because you are only ever going to see parts of the collection through it. When you only have bits of a collection up, then it has use as a teaching tool, as a teaching tool this is absolutely fantastic, but the academic researcher is interested in seeing things in their entirety, and I doubt many of us would have the confidence that the documents that have been selected are the only ones that are potentially useful or what we want to look at. On the whole we want access to the complete collection. Even if you get a quarter of a collection up we will still want to see the other three quarters.

Other users counteracted these concerns by suggesting that even sampled material can be of use, as long as the extent of the whole collections is made apparent:

User 1: There are some areas where that wouldn't matter anyway. For example in family history if you were doing parish registers, if you only did one year then at least that would be a year that has been done, which is 100 times better than nothing, as long as it is made clear the extent of the sampling then I don't think there is a problem. I think this is fantastic because you have eliminated the problem of illegibility with old handwriting by having the transcript and the other thing is that this is searchable. If you improved the search options further than this would be absolutely brilliant even if it only contained a limited run of data.

User 2: As long as you know what proportion of the material has been selected then anything is better than nothing. The problem is if you are left unsure as to what has been selected and what has been left.

There is no question that developing applications which deliver transcripts and images alongside contextual information is time consuming and costly. Realistically, it is impossible for archive repositories to divert core funding into such activities, and we envisage that some form of soft funding would be necessary for applications to be developed and implemented. Even when external funding is made available, limitations on resources may still mean having to make a case for transcribing and imaging only parts of collections. In such cases, implementers will need to think carefully on the implications of delivering limited numbers of transcripts and images from whole collections to ensure that such provision is going to remain valuable to users.

Cross over between scholarly edition and archive finding aid

One archivist made a valuable point about the nature of the demonstrator application and how it sits somewhere between being a scholarly edition of textual material and a finding aid based application:

In a funny sort of way I was more interested in this as a Surrey records society editor than I was as an archivist. I think because except where you have got very small collections, the amount of work in transcribing seems to mean that there are very few groups of archives in a generously sized record office that you could use this for. The exception being when you have volunteers transcribing particularly interesting material. It almost seems that this system is a replacement for a published edition almost, of the letters of George Orwell for example, so I looked at it more as a kind of book substitute than a kind of archival finding aid substitute.

Back to top5.9 Overall strengths and weaknesses of the demonstrator

When asked to comment on the demonstrator's weaknesses, the users commented on the limitations of the search functions as being the major negative aspect in the application:

The weakness is the search facilities you want more than just pre-defined indexes, more options

When asked to sum up the strengths of the demonstrator, the users all agreed that having the image and transcript together was the most important feature of the application:

User 1: It's the fact that this has the transcripts and images, that's what makes it. I don't think I have seen that before.

User 2: It is so vital to see both the transcript and the images together. That is absolutely great.

Connected to this recognition of the importance of having the transcripts and images were comments on the immediacy of access that the demonstrator provides:

User 1: I think also this is so quick and easy. You can view so many documents at once. My experience of researching in an archive is you have a long drawn out process of having to request your documents and then waiting for them to arrive, you have to look through them and then you find they didn't contain what you wanted after all and you have to start all over again. Whereas with this they are here instantly with just a few clicks

User 2: Yes that is right. You order up a box of archives, you flick through, you find there is nothing in there and you have to wait for the next one to come

User 3: Of course the other thing is not having to travel to the archive in Kent to view the material that I am interested in

The inclusion of information from the finding aids and authority records alongside the transcripts and images was also remarked on:

User 1: I think there is a lot of detailed contextual information there presented in a way that makes sense in relation to the document you are viewing which I see as a major strength

User 2: Yes I think the very detailed contextual information is excellent it all makes it very valuable. You are not seeing the document in isolation but are getting all of the information that surrounds it and makes it intelligible. Its such a great teaching tool

Back to top6. Summary and Conclusion

To conclude, the user testing has given us a valuable insight into what users want from online archive applications that are focused on the delivery of transcripts and images of archive documents alongside contextual information.

6.1 Search facilities

In regards to search functionality, our testing has revealed that users are not entirely convinced by searching that is solely reliant on using pre-defined indexes. The users' dissatisfaction was partly connected to the way in which this function was presented to them within the demonstrator application. The comments we received indicated that the design of the search input form was confusing and the accompanying explanatory information was lacking. This, coupled with a lack of descriptive information on the methodology employed by the indexer, left many of the user's in a state of frustration and confusion.

However, in the case of professional/occupational and education/training users (with academic backgrounds) it was not only the presentation of this function within the application that was problematic, but the actual function itself. These users expressed a fundamental concern that pre-defined indexes were forcing them to search in ways determined by the indexer who they instinctively believe to be inadequate. It was clear that these academics see the indexing process as an interpretive act and believe that relying on another individual's interpretation on the content of the documents will hinder rather than aid their ability to effectively use the material.

This group of users also stood out from the other participants in relation to their opinions on 'browse facilities' that would allow them to navigate through the hierarchy of the archive finding aid as a means of reaching the digital documents. Whilst the other users expressed either ambivalence or concern over the utility of this functionality, the users with academic backgrounds viewed it as a necessary requirement within the system. These users strongly expressed a desire to immerse themselves within the descriptions of the collections as a prerequisite to retrieving any documents.

The academics were also the most vocal in expressing a desire to be given as many search options as possible including free text searching; searching on descriptive information about the document such as its creator, title, id and date of creation; and advance search options including features such as wild carding.