UCL researchers take a sideways look at peripheral vision

4 March 2010

Links:

ucl.ac.uk/ioo/" target="_self">UCL Institute of Ophthalmology

ucl.ac.uk/ioo/" target="_self">UCL Institute of Ophthalmology

Researchers from UCL's Institute of Ophthalmology say what we can and can't see in our peripheral vision may not be the result of a random process.

As you read this, you may notice that the word directly in front of you is clear, but all the surrounding words are hard to decipher. For most people, this effect - known as 'crowding' - is not a problem.

However, for the millions worldwide who have lost their central vision through eye disease such as macular degeneration, it can make everyday tasks such as reading or recognising friends a challenge.

Crowding affects more than 95 per cent of the visual field, but we know very little about how it occurs, aside from the fact that it happens not in the eye, but in parts of the brain that deal with seeing. With far fewer neurons processing inputs from the peripheral visual field compared to our central vision, the brain simplifies these areas to represent more efficiently what is in front of us.

Researchers had previously assumed that crowding makes us worse at recognising things by making our peripheral vision more random. But Wellcome Trust-funded researchers at the Institute of Ophthalmology and colleagues from Harvard Medical School report today that this process is anything but random.

They asked volunteers to look out of the corner of their eye at a small patch of random visual noise (similar to the 'snow' seen when a television loses its signal). When the patch of noise was surrounded by striped patches all oriented in a particular direction, the volunteers reported the 'noise' to be similarly oriented. The results suggest that crowding is actually a process that makes the world appear more regular by essentially 'blending' nearby objects together.

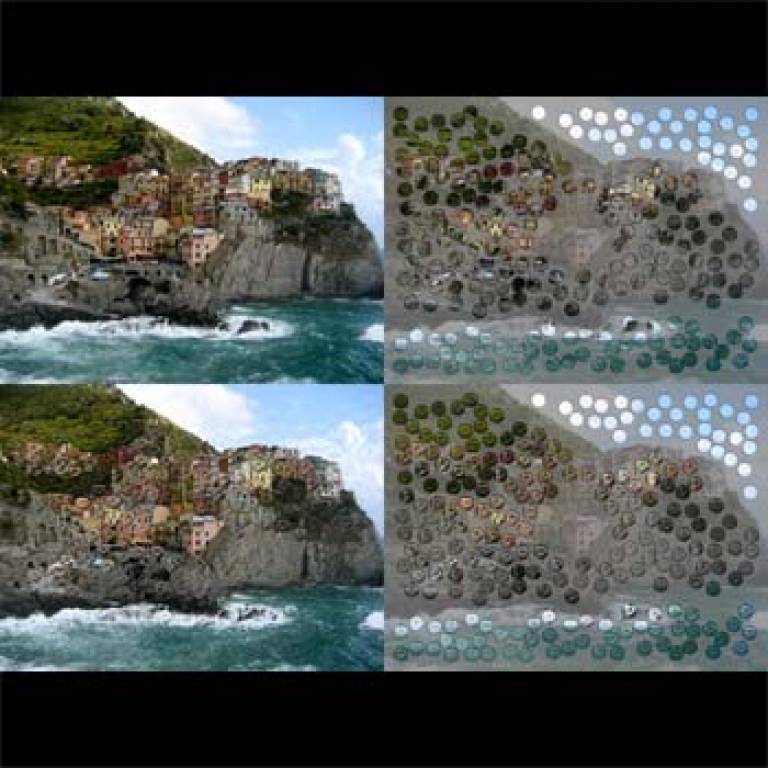

The researchers have used a real-world example to demonstrate the effect. Taking a photograph of a dramatic coastal village in Cinque Terre, Italy, the researchers 'scrambled' a large number of patches throughout the image by swapping individual pixels within each region. However, when one's eyes are fixed on the centre of the corrupted image (for example, on the central brown house), these 'noise' patches disappear and the image appears relatively undamaged. This image was recently named runner-up in UCL's 'Research Images as Art' competition.

Dr John Greenwood, from the UCL Institute of Ophthalmology, said: "We believe that this tendency of our brains to assume that the world is regular may have evolved because fewer cells in the brain are devoted to the edges of our vision compared to the centre. In other words, the brain is not capable of delivering anything more than a simplified sketch using these resources."

The researchers believe that understanding crowding promises to reveal much about how the visual brain works, and will also reveal the best way to present television images, text and the internet for people with damage to their central vision, for example through eye diseases such as macular degeneration and amblyopia ('lazy eye').

With amblyopia, for example, it has been suggested that crowding in the 'lazy' eye may occur in central vision in addition to the normal crowding in the peripheral visual field. Similarly, in macular degeneration patients lose their central vision and must rely on their peripheral visual field.

Dr Greenwood added: "If we understand when crowding does and does not occur, then we could potentially create text and images that are less likely to cause crowding. Similarly, if we can understand how things look when they are crowded, we could potentially generate text and images that could be recognised even when crowding has had an effect."

For more information about the UCL Institute of Ophthalmology follow the link above.

Image: Photograph depicting a coastal village in Cinque Terre, Italy, that researchers 'scrambled' by swapping individual pixels.

UCL context

Working in partnership with Moorfields Eye Hospital, the UCL Institute of Ophthalmology is one of the world's leading centres for eye research. The Institute is committed to a multi-disciplinary research portfolio that furthers an understanding of the eye and visual system linked with clinical investigations targeted to specific problems in the prevention and treatment of eye disease.

Moorfields Eye Hospital, Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children, UCLH, the Royal Free Hospital and UCL form UCL Partners, Europe's largest academic health science partnership.

UCL wins Fight for Sight research grant and PhD studentships

Close

Close