This webpage gives you open access to the competence framework itself, along with some brief background information (which helps to put the framework in context), and background documents for both clinicians and commissioners.

It is a good idea to read the background information and documentation, as this will help you to implement the framework to best effect.

Background information

- Information on the expansion of therapies included in the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme

- How the competence framework is structured

- Information on Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT)

Background documents

- IPT - Information for clinicians and commissioners: Essential reading for users of the framework. Explains the principles which guided the framework's development, and the ways in which it can be applied.

- IPT - Information for service users: What is IPT? What can service users expect if they are offered IPT

IPT competences framework map

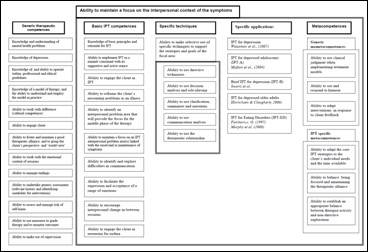

As described in the background document, the map shows the five domains of competence, and the activities associated with each domain.

The map is an overview - it is not the full list of competences. We have tried to make downloading the lists of competences as easy as possible, and you have several options:

From the map itself - placing the cursor over any of the boxes in the map links you to the competences. To see the full list of competences in each domain, click on the header (i.e. if you want to see all the competences for generic therapeutic competences, click on the box with this label) To see the competences associated with a specific activity, click on the relevant box.

To see the competence lists independently of the map (arranged by domain), click on the relevant link below:

- Generic Therapeutic Competences

- Basic IPT Competences

- Specific IPT Techniques

- Specific applications

- Metacompetences

Authorship of the IPT framework

The IPT framework was developed by Alessandra Lemma, Anthony Roth and Stephen Pilling, in consultation with an Expert Reference Group comprising: Jonathan Baggot, Anthony Bateman, Helen Birchall, Rosemary Cartlidge, Lorna Champion, Roslyn Law, Rebecca Murphy, Maria Okane and Mattius Schwannauer.

Information about the expansion of therapies included in the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme

The updated NICE Guidelines for Depression (available at www.nice.org.uk) indicate that IPT is an effective treatment for depression. In November 2009, the IAPT programme embraced this advice and committed to extending the range of psychological therapies available within IAPT. Alongside CBT (which is already offered) four other approaches are to be offered – IPT, Dynamic Interpersonal therapy (DIT), Counselling for Depression and Couple Therapy for Depression.

While NICE recommends a range of interventions, based on a wide-ranging evidence base for the treatment of depression, the choice of therapy and treatment will be made at a local level with the full involvement of the client, supported by good quality information made available for service users.

You can find out more about the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies Programme by visiting https://www.nhs.uk/service-search/find-a-psychological-therapies-service/

The framework details the competences that staff delivering IPT for Depression need to demonstrate to work in IAPT services. The work to derive these competences was commissioned by the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme.

Why IAPT needs to identify the competences needed by therapists

The IAPT programme involves delivering high quality treatments, and this requires competent practitioners who are able to offer effective interventions. Identifying individuals with the right skills is important, but not straightforward.

Within the NHS, a wide range of professionals deliver psychological therapies, but there is no single profession of ‘psychological therapist’. Most practitioners have a primary professional qualification, but the extent of training in psychological therapy varies between professions, as does the extent to which individuals have acquired additional post-qualification training. This makes it important to take a different starting point, identifying what competences are needed to deliver good-quality therapies, rather than simply relying on job titles to indicate proficiency.

The development of the competences needs to be seen in the context of the development of National Occupational Standards (NOS), which apply to all staff working in health and social care. There are a number of NOS that describe standards relevant to mental health workers, downloadable at the Skills for Health website (www.skillsforhealth.org.uk).

A competent clinician brings together knowledge, skills and attitudes. It is this combination that defines competence; without the ability to integrate these areas, practice is likely to be poor.

Clinicians need background knowledge relevant to their practice, but it is the ability to draw on and apply this knowledge in clinical situations that marks out competence. Knowledge helps the practitioner understand the rationale for applying their skills; to think not just about how to implement their skills, but also why they are implementing them.

Beyond knowledge and skills, the therapist’s attitude and stance to therapy are also critical – not just their attitude to the relationship with the client, but also to the organisation in which therapy is offered, and the many cultural contexts within which the organisation is located (which includes a professional and ethical context, as well as a societal one). All of these need to be held in mind by the therapist, since all have a bearing on the capacity to deliver a therapy that is ethical, conforms to professional standards, and which is appropriately adapted to the client’s needs and cultural contexts.

Information on Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT)

IPT is a time-limited, interpersonally focussed form of psychological therapy in which the client’s social and interpersonal context are understood to contribute to the onset of and/or maintenance of depressive symptoms. It is aimed at:

- reducing the symptoms of depression and

- improving social adjustment and interpersonal functioning.

IPT primarily focuses on current interpersonal functioning and recent life circumstances rather than longstanding conflicts or problems originating in childhood. It is assumed that symptomatic distress is relieved by resolving current interpersonal problems, and vice- versa. For example, resolving a dispute with a work colleague might help someone feel less depressed, and in turn feeling less depressed will help them work more effectively on resolving the dispute.

IPT is a change-oriented therapy; it aims to help the client to change their interpersonal behaviour, rather than develop insight. It focuses on relationship problems: on helping the person to identify how they are feeling and behaving in their relationships and then trying out new ways of interacting with others. When a person is able to deal with a relationship problem more effectively, their depressive symptoms often improve.

In practice IPT seeks to maximise the benefit of working in a time-limited manner by maintaining a “here-and-now” perspective on recent, recurrent or even chronic mood difficulties, and by framing the intervention around one of four interpersonal problem areas (role transitions, disputes, grief and loss, and difficulties initiating or sustaining relationships).

IPT has three main phases, each with distinct tasks:

The assessment phase focuses on a collaborative review and integration of interpersonal functioning and symptomatic patterns to arrive at a focus for the work.

During the middle sessions interventions are targeted at one of the four interpersonal problem areas.

The final phase addresses issues of ending, with a review of progress and (because depression can be a relapsing disorder) a focus on relapse prevention.

A fourth phase (which aims to maintain a good outcome and support relapse prevention), is negotiated for some patients.

How the competence framework is structured

The framework describes the various activities which need to be brought together in order to carry out IPT effectively and in line with best practice. It does not prescribe (or indeed proscribe) practice; it is intended to support the work of therapists by articulating the knowledge and skills they need to deploy when working using this model.

The framework locates competences across five domains, and shows the different activities which, taken together, constitute each domain. Each activity is made up of a set of specific competences. The maps show the ways in which the activities fit together and need to be ‘assembled’ in order for practice to be proficient.

This map helps users to see how the various activities associated with a therapy fit together. It is not a hierarchical model, with some domains being more important or requiring more skill than others. Any intervention will require clinicians to bring together knowledge and skills from all of these domains.

The five domains are as follows:

- Generic Therapeutic Competences

Generic competences are employed in all psychological therapies, reflecting the fact that all psychological therapies, share some common features. For example, therapists using any accepted theoretical model would be expected to demonstrate an ability to build a trusting relationship with their clients, relating to them in a manner that is warm, encouraging and accepting. They are often referred to as ‘common factors’.

- Basic Competences

Basic competences establish the structure for therapy and form the context and structure for the implementation of a range of more specific techniques. This domain contains a range of activities that are basic in the sense of being fundamental areas of skill; they represent practices that underpin the modality.

- Specific Techniques

These competences are the core technical interventions employed in the therapy. Not all of these would be employed for any one individual, and different technical emphases would be deployed for different problems.

- Specific applications

Even within the same therapeutic approach there can be slightly different ways of assembling techniques into a ‘package’ of intervention. Where there is good research evidence that these different ‘packages’ are effective it makes sense to describe them, so that clinicians know how these specific intervention are delivered.

- Metacompetences

Metacompetences are common to all therapies, and broadly reflect the ability to implement an intervention in a manner which is flexible and responsive. They are overarching, higher-order competences which practitioners need to use to guide the implementation of therapy across all levels of the model

More detailed information about the methodology used to develop competence frameworks can be found in:

- Roth, A. D. & Pilling, S. (2008) Use of evidence based methodology to identify the competencies required to deliver effective cognitive and behavioural therapy for depression and anxiety disorders. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 36, 129 –147.

Close

Close