Thylacines

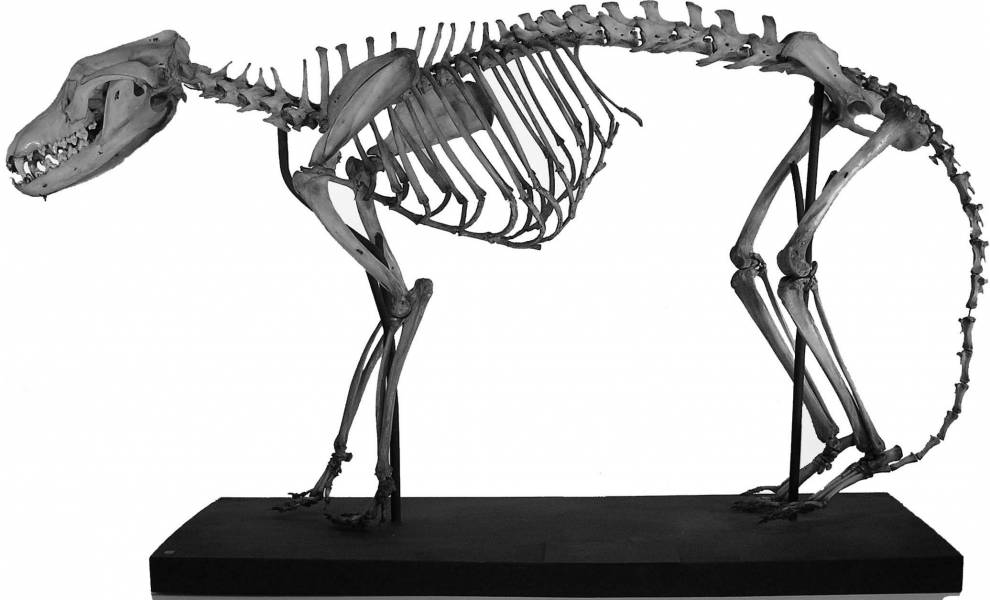

Thylacines are also called Tasmanian tigers or marsupial wolves. Although they do resemble wolves in outward appearance, these carnivores are not related to dogs any more than they are to any placental mammal. They belong to the group of marsupials which includes Tasmanian devils and quolls. Their adaptations as large carnivores are excellent examples of convergent evolution with the dog family.

Little is known about the behaviour of the thylacine, since no formal study of wild individuals had been made before their extinction in 1936. It is believed thylacines lived in small family groups. They have been described as hunting alone, running with a stiff-legged gait and capturing prey by tiring it out rather than ambushing it.

Conservation

Officially, the last thylacine died in the 1930s. Since then, however, there have been thousands of unofficial sightings and many believe it still exists. It has been claimed by local environmentalists that there is a government conspiracy to deny the survival of the thylacines in order to allow the old-growth forests to be felled and developed. It is very likely that most, if not all, of the recent sightings are of domestic dogs (there are no dingoes in Tasmania and only a handful of foxes have made their way over from the mainland, though a population is now becoming established).

The thylacine was hunted to extinction due to the belief that it killed sheep, although it is far more likely that the majority of Tasmanian sheep were taken by thieves and feral dogs. A government bounty was awarded to those who hunted thylacines, and this practice was not stopped until it was far too late. The bounty stood even when the animal was so rare that only one or two individuals were caught each year.

There were attempts to protect the species, however politics and lack of interest delayed action. The last known wild thylacine was shot by farmer Wilf Batty in Mawbanna in April 1930, and the last captive specimen died of neglect on September 7th 1936 in Beaumaris Zoo, Hobart, Tasmania. Ironically, thylacines were finally given full protection by the Australian government in that same year. There has been recent talk of cloning the thylacine using DNA from a preserved specimen, but the project was abandoned when it was determined that the genetic material was too fragmentary to be of any use.

Thylacines in the Grant Museum

The thylacine skeleton displayed in the Grant Museum was part of Robert Grant’s original collection and one of the earliest specimens to be housed in the Museum. He would have used this specimen in his classes during his time as Professor of Zoology and Comparative Anatomy.

Another thylacine specimen on display is preserved in fluid and is missing its head and paws. It may have lost these when the hunter that caught it collected his bounty or they may have been removed during dissection. On its back you can see the stripes. This specimen was one of Thomas Henry Huxley’s dissections and was part of his collection at the Royal School of Mines (now Imperial College London) in the late 19th century.

Huxley (1825-1895) was one of the first proponents of Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection. Known as “Darwin’s Bulldog”, he did more than anyone else to advance its acceptance among the scientific community and public alike. The specimen came to UCL when Imperial College closed its zoology collection in the 1980s. The Grant Museum is now the last remaining university zoology museum in London.

Read more about the Thylacine on our blog, including our post on Finding and Not Finding The Rarest Museum Specimens. You can also check out The Thylacine Museum and video footage of the last known Thylacine individual.

Close

Close