UG student Zahra Farooque selected as Regional Winner for Europe in the Global Undergraduate Awards

1 November 2021

We chatted to Zahra about her essay ‘Jogando Capoeira: African roots, Performance and Resistance in Nineteenth Century Brazil’.

1.Hi Zahra, thanks so much for talking to us! You were recently selected as a Regional Winner for Europe in the History category of The Global Undergraduate Awards 2021 Programme. This was for your final-year History Dissertation ‘Jogando Capoeira: African roots, Performance and Resistance in Nineteenth Century Brazil’- Can you tell us about more about this essay?

It is my pleasure!

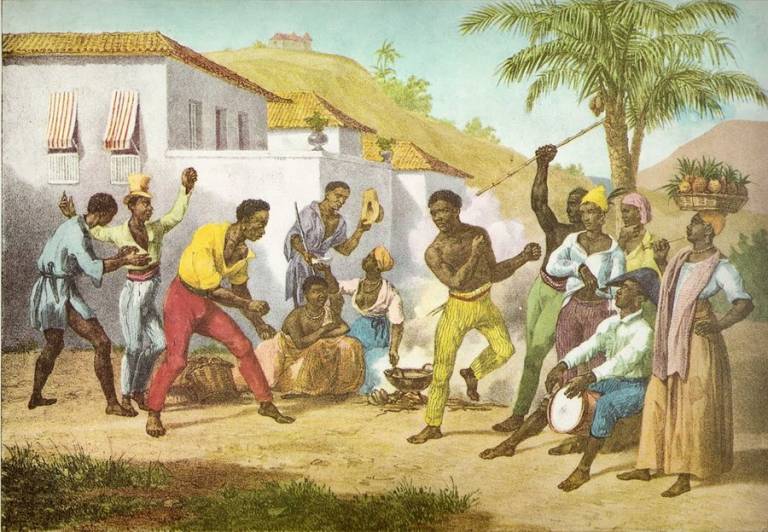

My dissertation explores the practice of capoeira in nineteenth-century Rio de Janeiro. Capoeira is a martial art that was developed by enslaved West and Central Africans and their descendants in Brazil. In my research, I focused on how enslaved Africans and their descendants practiced capoeira in Rio de Janeiro in order to explore the African roots of capoeira, the communities that were built around its practice, and its role as a form of resistance for Black people at the time. My aim was to think of capoeira as a coping mechanism for both freed and enslaved Black people in nineteenth-century Brazil, and to counter dehumanising narratives that position Black people as passive victims of enslavement and the racial hierarchical structures that existed around this enslavement In my dissertation, I incorporated Bourdieu’s theory of ‘habitus’ to reconcile the dichotomy between racial structures that Black people in nineteenth century Brazil had to contend with, and their own agency.

2.You wrote your dissertation in the Special Subject ‘Intellectual History from Below: Africans, Indios, and Women in the Iberian World 1500-1800’. Why (or how) did you decide to write your final-year History Dissertation on that topic?

As a martial artist, I had always been fascinated by capoeira as an art that was developed by enslaved subjects and disguised as a dance to avoid the detection of slave owners. I started to think about how capoeira fit within the wider discussions I had in my Special Subject seminar and began to form a more concrete plan on writing a dissertation on this topic. As someone who has used karate to build my own mental resilience, I wanted to explore whether capoeira was not only a way for enslaved subjects in Brazil to build their physical strength, but whether the practice of capoeira might also have helped build psychological strength and a sense of community within the harsh realities of the lived experience of enslavement. This topic related quite well to a particular seminar discussion on the importance of exploring the lived experience of enslaved subjects and their cultural, social and political legacies on modern nations, which are often overlooked. The regular meetings I had with Dr Chloe Ireton were really important in helping me to refine my ideas and figure out the structure of my dissertation. Once I had decided to draw on the theoretical lens of habitus to tie my work together, I felt more confident about using the fragmentary sources that were available.

3. Can you describe some of the historical sources that you analysed in your dissertation, and share with is some reflections about your experiences working with these primary sources and/or the challenges that you faced during the research or writing process?

Finding the primary sources to write my dissertation was quite challenging as there are not many that recorded detailed capoeira practices for the time period that I was exploring. The sources that I did find were written from the perspective of Europeans in Brazil and so did not accurately represent how capoeira was practiced. After discussing this issue with Dr Ireton, she encouraged me to think of the capoeira movements themselves as a primary source. This prompted me to use the depictions of capoeira games in European paintings as a basis of my analysis, which meant I was able to build a more complete image of capoeira’s place amongst Black communities in nineteenth-century Rio de Janeiro. In addition, I began to think about urban history, and I spent a lot of time thinking about the urban geography of nineteenth-century Rio de Janeiro, as I began to map where capoeristas lived in the city and the varied meanings of capoeira jogos within the urban context. I also drew on varied sparse accounts of capoeira that were sometimes featured in descriptions written by European visitors to Brazil and in police reports from the city of Rio de Janeiro. The assorted use of such different source types really challenged me as a historian, but made it all the more rewarding when I was able to bring the practice of capoeira alive in my dissertation.

4.How did the process of researching and writing this dissertation help you to develop as a historian?

The process of writing my dissertation made me more confident in my voice as a historian, especially when researching a topic with so few traditional archival records available to non-Portuguese speakers. Throughout the research, I explored a diverse range of sources that I had not interacted with before, including paintings of urban scenes, police reports, traveller’s accounts, and urban maps of Rio de Janeiro, all which really helped me to build a picture of how enslaved and free Africans practiced capoeira in the city. Once I had located pertinent primary sources, and thought about the theoretical framework of habitus, I also developed a better grasp of how to use theory in my work. Overall, the skills I used to research and write my dissertation made me a more well-rounded historian and was a great way to conclude my undergraduate degree.

5.That sounds really interesting! Why did you decide to submit your essay to the Global Undergraduate Awards on this topic?

During my dissertation feedback session with Dr Ireton she shared the competition and encouraged me to submit my dissertation. I thought that it would be a great way to share my work on this important topic that I was really passionate about. It has been a very rewarding experience to have my work acknowledged by a wider community as this also means that people are recognising the importance of challenging traditional narratives and giving a voice to those who have been disregarded by history.

6. This month is Black History Month, and the history of slavery is obviously central to this. Why do you think Black History Month is so important?

As someone from a minority ethnic background I know how important it is to have ones history accurately represented. Part of my own motivation to study history was to get a better grasp of my own place in the world. I am not Black so I feel I have limited authority to speak on this subject, but what I can say is that I recognise the importance of Black History Month in order to properly present the history of Black people. It is important to understand the negative impact of misrepresenting the history of Black people, especially when considering enslavement and the dehumanising narratives that have dominated historical discourses. Through my research for my dissertation I gained a greater awareness of just how side-lined Black voices have been throughout history. Indeed, Black History Month is important to bringing to the forefront the centrality of Black history to that of Western history in general. Unfortunately, we often we think of Black history and, for instance, British history, as two separate subjects, but Black History Month allows us to understand and remember how both are interlinked. The important thing is not to forget about ‘Black History’ once Black History Month is over and instead to integrate Black History within mainstream history.

7. What tips and advice would you pass on to other students about life as a historian at UCL?

It is so important to take advantage of the diverse range of modules available in the history department in UCL. I would encourage students, especially those in their first and second years, to study new histories they have not previously encountered in order to discover new interests and approaches to historical work. For instance, taking Dr Ireton’s Black Atlantics in the Global South Research Seminar module in second year, on a topic I had never encountered before was so valuable to me as a historian as I become more intentional about the kinds of historical narratives that I prioritised in my work and the wider impact this had. Essay writing is also a key part of this degree, so having the confidence to try new writing styles and structures is another important part of developing your skills as a historian and one I wish I had started earlier.

8. You have now graduated from UCL History! What are your plans for the future?

At the moment, I am hoping to build a career in the Civil Service, and I am also excited to continue engaging with new scholarship in the field of Black history as there are currently many historians who are doing really important work.

Image: 'Johan Moritz Rugendas, ‘Jogar Capoeira ou danse de la guerre’, 1825' from https://www.torch.ox.ac.uk/event/culture-and-resistance-in-the-lusophone-world

Close

Close