Looking up, by Prof Lucie Green

Posted 22 October 2020

For most people, looking up in the context of the research field I work in (space science) means turning our gaze towards the stars at night. We’ll often see advice that keeping an eye out for clear skies and finding somewhere with as little light pollution as possible will deepen the experience. Perhaps, use a deck chair and lie back as your eyes become dark adjusted, so that the Milky Way and a multitude of stars emerge before you. And this is good advice. But whatever environment you find yourself in, even in a city, there are things to see in the night sky and reasons to take some time out to look.

When I step outside my house I am surrounded by buildings, trees and a hill that means I actually only have a fairly small patch of the sky visible above, but I’ve found that this is all I need. During the COVID-19 pandemic this view has provided solace. The early days were dominated by Venus shining brightly in the western sky after sunset. Each evening, from my hallway window, I would watch it track across the sky, seen in my binoculars against the background stars, before it moved too close to the Sun to safely view.

A new comet appeared – faint and wispy above the tree line. I felt triumphant each time I spotted it. A challenge amongst the street lights.

In such difficult times, looking up has provided escapism. A reason to engage with something bigger and out of my control. But in a good way.

Looking up leads to activism too. I spent several nights waiting for the SpaceX Starlink satellites to pass over overhead. They were very prominent at the start of the lockdown. These satellites aim to provide global internet access, a laudable aim that requires a network of 12,000 of them. Many, including myself, have looked at the satellites crossing the sky like a string of pearls and felt concerned about what this means for future generations of stargazers and the “photo-bombing” that will happen, ruining images taken at observatories around the world and in back gardens of enthusiasts. The action that followed by those with a passion for the night sky was swift and to SpaceX’s credit they have listened and responded with measures to reduce the brightness of the satellites. Now, they should be barely visible to the naked eye and the conversations between SpaceX and the astronomy community bode well. There is still more do, but things are looking up.

One important area that needs more activism is how we make looking up a truly inclusive activity. Recently I learned about the trailblazing work of people like Dr. Wanda Díaz-Merced, at the Harvard Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, and Dr. Nic Bonne at the University of Portsmouth. Both have developed novel ways of using sound and touch to open up the night sky to people who are visually impaired. Wanda played me the sounds of a gamma ray burst and a cataclysmic variable, and we discussed how everyone has the right to access the inspiration of the night sky and be part of the effort to gain new knowledge about it. I realised that looking up isn’t actually about the “looking” at all. It’s about community, equity, and a drive to feel the thrill of learning more about the fascinating Universe we live in.

‘Looking up, looking back, looking out, looking in’ by Osnat Katz

Posted on 21 October 2020

We often associate looking at space with the act of looking up – going outside on a cold night and searching for stars, planets and galaxies. We’ve been finding meaning in the sky around us for thousands of years, with cultures around the world telling stories about the skies above us. We still try to find meaning today; modern astronomy developed out of astrological attempts to understand how reading the stars could help us here on earth, and early space scientists around the US, Europe and Russia were influenced by the writings of Russian philosophers.

For my PhD research, I study the history of the Mullard Space Science Laboratory – the UK’s oldest space science research lab. From a stately home deep in the Surrey countryside, about 200 people build instruments that will one day launch on spacecraft. They monitor those instruments out in space, and their flight spare twins here on Earth, for decades at a time. They also comb through the data produced out in space to learn more about our Solar System and our Universe. They, too, are making meaning out of looking up – but in a different way. Seeing with the naked eye, or with telescopes or binoculars, is something far removed from monitoring the data transmitted by an instrument in space.

I write what’s called social and cultural history – instead of trying to understand the Mullard Space Science Laboratory through looking solely at scientific papers, I look at what people think, feel and believe about MSSL, and I do that through sitting them down and interviewing them. As part of my work, I wanted to investigate how people felt about the science and engineering they did at MSSL, but also how they felt about the social side of their lives.

What I found is that even when people wanted to separate their work from the culture of MSSL, many of them couldn’t – to them, space science and life at MSSL are so closely bound up that discussion of one inevitably led into the other. An anecdote about working on an instrument would involve the people working on it; a story about the people working at MSSL would slowly lead into a story about what they worked on. As we built up trust through sitting and talking, people would tell me about other memories – ones that were more difficult to put into words or turn into easily intelligible stories. These were almost inextricably linked to certain instruments, usually ones that they’d worked on.

At MSSL, people’s understandings of “looking up” become intensely physical. From the academics’ offices to the great mechanical drawing office, and from the cramped electronics workshops to the long mechanical workshops where the instruments are put together, the people who work at MSSL are surrounded by the things they’ve made and are making. They’re also surrounded by the products of the things they’ve made and are making: the data sent back by space instruments and the flight spares kept in MSSL’s clean rooms. To look up at the sky, they have to look inwards within the lab – and even inwards within the instruments, as certain parts of the instruments are still handmade.

By now, we are used to images from space telescopes such as Hubble, and we’re quietly waiting for the James Webb Space Telescope to launch. Many of the instruments built by MSSL aren’t true imaging instruments, but detectors for electrons, ions, plasmas and photons. They don’t produce data that’s particularly easy to understand for non-specialists – something that came up more than a few times in interviews when I asked about describing findings and results. Although they took pains to stress that their results didn’t look like Hubble images, and often found themselves explaining that they were working in a completely different environment or at a completely different time – one where they may have lacked very basic knowledge of astrophysical processes – the people who worked on those instruments could “see” the data in a way that I could not. They would proudly tell me about the achievements that they made and the things that they saw – X-ray images of the Cygnus Loop, Cassini’s discovery of negative ions around Saturn’s moons, heavy ions around the Sun. They looked up at the Sun, stars and planets through instruments they had looked in on, and they looked back on their memories as I witnessed.

At MSSL, looking up at the sky is a multifaceted endeavour, one involving deep and frequently intense connections both with instruments and with other people. In looking up, people at MSSL look inwards towards the fine details of the instruments and outwards towards the people around them.

‘Looking Up’ by Paddy Edgley, COSS Assistant Director

Posted on 19 October 2020

In the discussion we had at the start of this month, which christened our centre, we heard from a group of artists, writers and scientists whose work involved thinking through the earth as a planet or a globe. More precisely, they discussed how we might attain new and different perspectives on our planetary home, which can help us to reconsider our relationship with it, and our taken-for-granted assumptions about our place in the cosmos. In everyday life our experience of our planet is as a vast, immovable ground on which we dwell, while the sun seems to move through our skies. The accounts these speakers offered to us of earth sought to reorient these views, and help us in “thinking humanness from elsewhere” (Valentine 2017: 185)

There is something deeply Copernican about this work. It helps us to come to terms with a universe which is, at times, radically at odds with the way in which we experience it. Our everyday experience is, in a sense, misleading, obscuring the true nature of our home. Our understanding, in this sense, needs reorienting. These perspectives on our world invite us to join Copernicus, as the “mover of the Earth and Stayer of the Sun and the Heavens” (Blumenberg 1987: 264).

This month, we return to earth and reconsider that perspective from the ground, and “looking up” at the sky. While the perspective from above Earth—first as atlas, then as world image—deepened our capacity to contextualize ourselves within the cosmos and render our place anew, our relationship with the universe at large begins with this tilting of our head and squinting of our eyes. Looking up, in one way or another, is how we know what we know about the cosmos.

My interest, and the focus of my doctoral research, is in cosmology. Specifically, I am interested in thinking about scientific cosmology anthropologically, understanding the cosmology of physics as an anthropologist. That is to say, rather than necessarily being interested in the matters of fact about the universe—its structures, processes, history, forces and substances—I am more interested in how people go about engaging with the universe, the conditions of that engagement, and its social and cultural implications. I am less interested in whether those engagements offer us the one, true, definitive image of the cosmos, and more in what people take and interpret those perspectives to be. The view of earth from above, and indeed the vistas we are presented with when we look up, are interesting to me precisely because they are taken to be just that: some people consider them to be ‘truer’ views of the universe for their capacity to challenge our quotidian experience of the world.

For this reason, my investigation is primarily into “looking up.” Particularly, I am interested in amateur astronomers, how stargazing affords them a particular perspective on the universe, and how that informs our understanding of ourselves. To a large degree, looking up can be said to elicit a similar effect to the view from above. Science communicators such as Neil deGrasse Tyson and Carl Sagan, alongside informants, talk about the “cosmic perspective” it helps to attain, seeing the world not as a human, but, ostensibly, on its own terms. In the second book of Douglas Adam’s classic Sci Fi comedy series The Hitchiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, coming to terms with a universe that is so much bigger than ourselves is seen as not only impossible, but a form of mental torture (156). Such comprehension is, in this view, simply beyond humans.

Astronomers, however, describe this experience as therapeutic rather than torturous. There is a kind of sublime in the juxtaposition between these vastly different scales (Kessler 2012). In such a context we, or projects, and our anxieties, become trivial. As Carl Sagan famously noted while reflecting upon the Pale Blue Dot image of the earth, taken from 6 billion kilometers away, “it is said that astronomy is a humbling and character-building experience. There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world.”

The Pale Blue Dot image, taken by the Voyager spacecraft on February 14th 1990 as a part of the family portrait. The Earth can be made out as a point of light in the leftmost chromatic aberration. Credit NASA

For me, thinking through our relationship with outer space in terms of “looking up” helps, ironically, to ground our discussions of cosmology. It reminds us of what is missed by these global and cosmic perspectives: that they are made and shared down here. Even if these images are not always rendered from a human perspective, they are always produced and interpreted by people. Thinking about stargazing doesn’t just mean engaging with space, but also being attentive to the conditions here on earth that make viewing possible, or difficult. These considerations tie our space-bound projects to traditions, practices, and ethical issues here on earth, and remind us that there are things that should not be trivialized or overlooked by the cosmic perspective. This raises the question of what other taken-for-granted assumptions linger beneath this wonder. The ways in which our would-be pristine space projects are dirtied by earthly and particularly colonial histories have already been discussed by thinkers like Peter Redfield (2002) and Alice Gorman (2005). By attending to the local and “provincial” aspects of stargazing, and the practice of “looking up,” we might ask what else we miss when we look at the world from a cosmic perspective.

Works Cited

Gorman, A. (2005). “The cultural landscape of interplanetary space.” Journal of Social Archaeology, 5(1), 85–107.

Redfield, P. (2002). “The Half-Life of Empire in Outer Space.” Social Studies of Science, 32(5), 791–825.

Valentine, D. (2017). “Gravity Fixes: Habituating to the human on Mars and Island Three.” Hau: Journal of Ethnographic Theory, 7(3), 185-209.

Blumenberg, H. (1987). “The Genesis of the Copernican World” MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Kessler, E. A. (2012) “Picturing the Cosmos: Hubble Space Telescope Images and the Astronomical Sublime.” University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, MN.

Earth, by Nicola Baldwin

Posted on 27 September 2020

HOSPITALFIELD JOURNAL – ‘Woman From Mars’, writing the first draft

I’m writing this on 26 September, on the train from Arbroath, leaving Hospitalfield House, where I’ve just completed a two-week cross-disciplinary residency, which began on 16 March…. Cut short by lockdown, suspended for 6 months while the House was closed. The replanting of the garden allowed a trial reopening, and the last (lost) group were invited back.

I was there, thanks to an MGCfutures bursary, to write the first draft of ‘WOMAN FROM MARS’, about Helen Sharman, the first British Astronaut, who traveled to Mir space station in May 1991 on the final mission of the Soviet cosmonaut programme.

The play I’m now finishing has changed in several ways – including the title. Returning to Hospitalfield brought into focus what an intense, strange experience, that first residency delivered; the five of us, mostly alone in the house, washing and sanitising hands, doorknobs, kettles before touching, kettles after touching, trying to concentrate on our own work and wondering if the decision to come here would kill us. Some of us getting panicked emails, texts and calls from home, to come home – texts and emails from our jobs, not to come back.

I kept a journal as I planned to write the first draft over an 8-day burst, as a dramaturgical re-enactment of Sharman’s Soyuz TM-12 mission itself. On 23 March I returned to London and caught COVID on the trip. Crossing the Tay Bridge I shot a short video of the first morning of lockdown.

Nicola Baldwin, 26 March, (I’m crossing it again now)

‘WOMAN FROM MARS’ HOSPITALFIELD JOURNAL, Nicola Baldwin March 2020

My writing residency at Hospitalfield runs from Monday March 16 – Sunday 29 2020

Helen Sharman on Mir mission from Saturday May 18 (launch) 1991, returning May 26.

I am synching these notes on writing the first draft to same dates of month.

First Briton in space, cosmonaut Helen Sharman, May 1991.

Monday March 16 2020

The project of this fortnight is to write a first draft of a new play, while using the Interdisciplinary Residency to reflect on my practice. Firstly, by working through a schematic set of activities which foreground the process of dramatic creation and explore how structure and story interact; secondly, by talking with fellow Residents, visual artists, about their work. The first intent is informed by the 12 biological and chemical experiments Helen Sharman performed during her 8-day mission to Mir. The second intention, by the fact that as a playwright and scriptwriter, I work along the axis of time – narrative drama, whether live or recorded, is received in real time, and my practice resolves around creating temporary sequences of events. By using specific approaches to constructing narrative, and the opportunity to work in a large blank space I can make my working process spatial and visual. I will be able to ‘see’ how I work.

Tuesday March 17 2020 / MAY 17 1991

Helen Sharman: At Baikonur Star City. Eve of launch, packing final kit for experiments.

Me: At Hospitalfield Interdisciplinary residency. Unpacking notes and setting up workspace. Initial plot question. How to expand an existing short play, wherein the moments and dramatic twists are baked in. ‘Miss (Stella) Shaw’ is both integral, and problematic. She is literally an interloper, but will she split focus too much in the full draft? Initially drawn to frame story of another ‘Helen’ plucking up courage to tell her mum ‘Mrs Shaw’ about moving to Ukraine with ‘Sergei’ in 2021, with final twist of ‘Helen’ being schoolkid who received Mir seed from Helen Sharman. For about 24 hours this idea feels a quirky and dramatically bold way to tell my story. I’m trying to rationalise the existence of Miss Shaw in space to make the story about the transaction with Helen and Miss Shaw. Also to protect my play if the real Helen Sharman decides she really doesn’t want the play to happen… If I do have this double narrative frame; of Miss Shaw on Mir being the impetus for Helen to tell her story; this is turn framed by another ‘Helen’ whose story this really is…. We still don’t explain Miss Shaw. But it would be:

‘HELEN’ USES THE STORY OF HELEN SHARMAN MIR MISSION TO EXPLAIN TO HER MOTHER WHY SHE IS MOVING FOR NEW LIFE IN UKRAINE WITH ‘SERGEI’.

Wednesday March 18 2020 / Saturday MAY 18 1991

Wednesday March 18 2020 / Saturday MAY 18 1991

Helen Sharman: Following various checks, medicals, rituals, successful launch Soyuz TM-12.

Me: Break down structure of existing short script onto post its and go through accumulated notes on current draft what needs to change, where to expand, what rings false. Read again sections of SEIZE THE MOMENT (Helen Sharman ghost-written autobiography) on the Mir Mission. Read again about the training and preparatory build up.

Get bogged down on tone / intent. Troubled by responsibility to my subject (Helen Sharman); the more I got to grips with her character, the more I understand why she wouldn’t approve my approach. I reject the (double) frame story, which coming into this residency seemed so appealing. The actual story of Helen Sharman is enough; stuffing it into a washing-up glove of kitchen sink drama is folly. Really I should be breaking it down. As Experiment 1, I approach the narrative in a ‘straight’ telling, powered by her character motivation and sketch a bash-draft of the story from a single premise….

I think of

HELEN SHARMAN ACCIDENTALLY HEARS AN AD FOR AN ASTRONAUT AND OVERCOMES MANY OBSTACLES TO REACH SPACE.

Or, even…

HELEN SHARMAN RESPONDS TO A RANDOM ADVERT FOR ASTRONAUT AND OVERCOMES MANY OBSTACLES TO ACHIEVE 6 DAYS OF WORLD PEACE ON MIR.

But… Sharman is not a dramatic character, however in order to tell the story ‘straight’ I need to dramatize her; i.e.. interpret her motives and invent obstacles (e.g. initial dislike between her and Sergei but in the end, she wins his respect; her being fearful and useless on initial Soyuz trip, floundering and the other 2 telling her to go away, before them ultimately bonding etc). I kind of think both these things may be true, but to tell the story this way requires narrative seeding, potentially more distorting of the ‘true’ experience than my existing framing device.

She’s rationalist, experimental, measured. An introvert with sense of fun with small groups of friends (at Star City); self-contained and happy alone. A typical scientist? Why does she apply? What does she want?

She’s curious. To see what its like, what would happen; to see if she can.

She loved sport, activity and, though she loved learning, hated much at school. Her mantra as a child, I Can Do It. Enjoys challenges. Yet introvert. Determined, and determinedly ordinary. An ordinary person who decided to have a go, and having decided, gave it her best shot. She’s very aware of gender in selection process, but determined others will not be, and won’t go there herself. She calculates her chances as a woman, without being a feminist. Factual response. Herself, as person with strengths. A unit.

Thursday March 19 2020 / Sunday MAY 19 1991

Thursday March 19 2020 / Sunday MAY 19 1991

Helen Sharman: on Soyuz TM-12 travelling towards Mir. Regular work/ checklists. Busy.

Me: Wake up feeling terrible. Not physically but emotionally jangled. Been building inside me, or rather outside, the situation with COVID-19 pandemic which I have been furiously blocking out, invades my dreams and on waking up, my thoughts. I worry about home, about self-isolating in London if I even get back; about whether I should try and get to Yorkshire. Parts of last 2 days occupied emailing actors to confirm cancellations – THE DUCHESS, the Waste play, workshops for WOMAN FROM MARS, total closure of UCL. All this intrudes and writing anything starts to feel pointless. What’s the point of writing a play when theatre is in ruins? I commit to paying all the actors. Will I really get through this? Financially? Physically?

To calm myself and simply get something done I explore gaps in the story from existing short version. I do a timeline of her backstory from hearing ad until Soyuz mission itself, and go through details of her time on Mir, particularly the purpose and nature of her experiments.

As Experiment 2, I plot some basic dates around situation in Eastern Europe, collapse of Berlin Wall, of Soviet Union. In these stories, I find parallels with my uncertainty about the world outside, the empty shelves, paranoia, feeling of apocalypse. I think about Helen Sharman’s comment about learning Russian and why pointing at things not an option; ‘you might be able to go into a shop in Italy and point at a cheese, but after queuing for hours in Moscow snow to enter a shop where the shelves are empty, you have to be able to explain to the shop assistant what you are looking for’. I think again that Helen Sharman’s extraordinary achievement is not simply being selected as a Russian cosmonaut, but also living in Russia for 18months. Also, her constant assertions about being an ordinary person, from an ordinary family, with ordinary childhood – no longer seem just like covering her privacy. There’s almost something political about insistence, and I wonder if she appreciated the Soviet ideal of merit?

In the evening we screen THE TWO POPES film against the wall – written and directed by playwright turned screenwriter Anthony McCarten (THEORY OF EVERYTHING). It’s very like a play, but with enormous set pieces; Ratzinger’s character isn’t explored until we see him coming to believe Bergoglio should be his successor. It’s interesting for me being based on real people, and very recent history – reminding me how little we know of anything behind news headlines and what a pleasure it is to revisit this news/ history as story. Again the idea of approaching it straight; yet the flourishes of THE TWO POPES are the voice of the writer, the structure, choices and

McCarten’s pacing are what makes the film a success.

In my notebook I go over the old writing questions:

Investigate what you’re really writing. Your idea. What’s it about?

Human contact? Finding and losing oneself?

Whose story is it? What does she want? Why can’t she have it? What must she figure out?

WHO ARE YOU? WHAT IS YOUR THRESHOLD?

DO YOU STAND FOR THIS, OR SOMETHING ELSE?

Friday March 20 2020 / Monday MAY 20 1991

Friday March 20 2020 / Monday MAY 20 1991

Helen Sharman: Arrival at Mir. Perilous docking, potentially catastrophic but dealt with. She experiences no fear because, from emergency training, took a measured view of risks.

Familiarises herself with radio ham equipment. Wrote at the time ‘Ace evening’.

Me: Today I get to grips with story, doing a bullet point list. My previous bullet list was always coming up with a ‘straight’ telling of events, because I was struggling to work through MISS SHAW as a consistent narrative. Now I take ownership of the story. It doesn’t matter what anyone might think, further down the line, what matters now is what I think. I decide my existing short version is broadly Act 1, though travel of characters through story is patchy. ‘Authenticity’ will come from working them in properly. The gaps and development needs to become the rest of the story. I think about where to put the launch sequence and the overall flow of visual set pieces. Then I think about what it means that this matters….

I fret about structure. For Experiment 3, I go back to Stephen Jeffrey’s book, and break the story as a 3 act structure – journey there, Mir, journey home. Jeffreys calls it the ‘magic trick’: Act 1 = The Pledge (an ordinary pen); Act 2 = The Turn (turn it into a bird and watch it fly off\) Act 3 = The Prestige (bird returns and turns back into a pen).

Jeffreys quotes David Edgar, that you can reduce every story to a single sentence, with a ‘but’. And if so, it’s:

HELEN SHARMAN DEFEATS EXTRAORDINARY OBSTACLES TO REACH MIR BUT DISCOVERS HER HARDEST CHALLENGE WILL BE COMING HOME.

That, marvellously, is exactly the story of the play. True to the situation and stakes of the drama, plus there is evidence of this in her accounts of Mir, where her most personal comments are about her reluctance to return to earth. So, it’s not the trivial fear of doing the broadcast to children, but what comes after, in the rest of her life, that is the final challenge?

The last thing I do is build a 3 Act structure with my post-its on 3 A2 sheets of paper, using the existing breakdown, some of the real timeline, and key notes for areas to expand.

After I’ve gone up to bed I set-up Experiment 4, a Myers-Briggs personality test for Helen Sharman, she comes out ISTJ, Introvert, Sensing, Thinking, Judging.

That night I also have an ending come to me as I am falling asleep, which doubles down on Miss Shaw, and leaves us with Sergei; for Helen appear back on Mir in his imagination, meeting Yuri Gagarin – who is not there either, but is Sergei’s version of Miss Shaw. I’m owning the bonkersness of my story, but also flipping it to say something about isolation. Not sure if this final twist will come out in the wash, but for today it gives me a light at the end of the tunnel.

Early next morning, I write:

Keep Stella Shaw, not as framing, but for character & human warmth

Expand and make truer Helen’s training and selection.

What real obstacles?

Soviet Union. Yuri Gagarin!

Blast Off later

It takes longer to conduct the experiments, they are contradictory. Results non-linear.

Her growing relationship with…? Miss Shaw?

Develop Anatoly – show this later?

Take seriously the final conversation with Sergei

Danger of return.

Remember that, Anatoly returned at the end of his mission as planned, 5 after months. Sergei had to remain aboard Mir, since the nation responsible for returning him to earth, the USSR, had ceased to exist. Newspapers round the world dubbed Sergei, ‘the last Soviet citizen’. People wondered how he would survive the solitude, which in the end, after 8 months, was the longest (then?) of any human in space. Treadmill. Helen – meet Yuri.

All life is chemistry and the people we meet, places we go, things we do, change us.

Saturday March 21 2020 / Tuesday MAY 21 1991

Saturday March 21 2020 / Tuesday MAY 21 1991

Helen Sharman: First full day’s work. Time suddenly feels short. Goes looking for cameras and trying to locate and set up her various experiments on the crowded Mir space station.

Me: I wake up feeling really positive. It’s our first day (as residents) alone in the House. Thursday was my when time started feeling short, when I was panicking I should be elsewhere. Today, time feels under control. I plot out the Myers-Briggs ideas from last night – Experiment 4 – and am pleased and surprised, that under this system, Helen is:

HELEN – ISTJ – INTROVERTED, SENSING, THINKING, JUDGING

Quiet, serious, earn success by thoroughness and dependability. Practical, matter-of-fact, realistic, and responsible. Decide logically what should be done and work toward it steadily, regardless of distractions. Take pleasure in making everything orderly and organized – their work, their home, their life. Value traditions and loyalty.

After my initial victory over my time, I allow myself to fully occupy my (work)space. I disassemble the 3 Acts from paper and use the long bare wall to begin assembling the whole sequence of the play as a single line, loosely as 3 Acts. For the first time I see the play spread out.

I’ve still really only got an Act 1, but the shape of the rest is clearer, and what I need to fill the gaps with is lurking, unsorted, among the post-its and timelines on the other wall.

All I need to do is to work on those ideas with felt emotion, to make them cross the room.

I think about the ‘shape’ of the dramatis personae; the relationship between Helen and Sergei. That crucial conversation on the final night; his conversation with Musa and Viktor before their departure home. I think I am finally constructing an engine to make the play fly – though I still don’t know where to.

I’m not totally convinced by my 3 Acts, because I know the launch needs to be my mid-point – visually, sculpturally – and I am interested to unpick how I know this, because it is anti-chronological, and suggests a deeper image system, as if crystalised fragments of the ‘real’ play are forming in the mix and bubbling to the surface. I need more sense of stakes and decision, in order to increase the boil. It’s the same problem as before, that real life is not narrative, and though Sharman’s story absolutely fits every element of story I need her to embody, I need to translate this into beats of personal obstacles, poor choices and failures which she overcomes, not let them simply be circumstance. This will include her interaction with other characters. I don’t feel I can develop those interactions clearly until I work out what I want them to do.

I plan Experiment 5, to test for archetypal structure, using 7 Basic Plots (Christopher Booker). I think about Quests. I remind myself that, in an archetypal Quest:

The Call Kickstarts the plot and gives the hero a mission to accomplish.

The Journey over enemy territory, obstacles pop up left and right; monsters (kill/escape), temptations, a rock and a hard place or journey to the underworld.

Arrival and Frustration She’s so close! She can see the Emerald City! Oh, wait, the Wizard won’t help them until they kill the Wicked Witch of the West. Still some work to do.

The Final Ordeals Now the final tests. A set of three? She is the only one who can complete the final test. Success! An amazing escape from ‘death’.

The Goal she has completed quest and gets treasure/ prince/ trip home. Holy Grail.

It’s not exactly how my story will play out, but looking at it as a quest, something clicks into place. I add Quest beats into my basic 3 Acts. The challenge now – and the exact place I should be at this point in my 8-day ‘Mission’– is determining the significance of any chunks of history and material I am putting in; placing them to make the story resonate.

If I continue the Quest Experiment, into characters, I discover that she needs:

- A close friend who loyal to our hero, but doesn’t have much else going for him or her;

- A sidekick who is polar opposite of the hero mentally, physically, and emotionally;

- A balanced party of brains, heart, and strength who support the hero, or who count the hero as one of their own.

In the short version I made Sergei her friend and ally. I toyed with the idea of making him an adversary whose respect she wins, rejecting this for being presumptive, but I think there’s probably truth in it. Certainly for the story, his authority is essential. In the short version he’s like a sidekick, but they are more similar than opposite. From her writings, its clear that Anatoly (‘Tolya’), who started training at the same time, and learning English as she was learning Russian, is her sidekick in the mission – not the remote, comic character he was in my short version. I decide – without any reference to his actual personality and traits – to see what happens if I make him the polar opposite of Helen’s Myers-Briggs, and it comes out as:

TOLYA – ENFP (HER OPPOSITE) EXTROVERT, INTUITIVE, FEELING, PERCEIVING

Warmly enthusiastic and imaginative. See life as full of possibilities. Make connections between events and information very quickly, and confidently proceed based on the patterns they see. Want a lot of affirmation from others, and readily give appreciation and support. Spontaneous and flexible, often rely on their ability to improvise and their verbal fluency.

Helpfully, and remarkably, this chimes with everything Helen has said about Tolya – right down to his keenness to practice English, and instances of him improvising fixes on board.

For Sergei, I pick the personality type of a Commander wherein his Myers-Briggs would be:

SERGEI – ENTJ (CONNECTS THEM) EXTROVERT, INTUITIVE, THINKING, JUDGING

Frank, decisive, assume leadership readily. Quickly see illogical and inefficient procedures and policies, develop and implement comprehensive systems to solve organizational problems. Enjoy long-term planning and goal setting. Usually well informed, well read, enjoy expanding their knowledge and passing it on to others. Forceful in presenting their ideas.

What’s useful about this, is that I’m sticking close to Helen’s own descriptions of herself and what people have said about her, to create a character based on her authentic personality. I’m then ‘making up’ the personalities of Sergei and Tolya to fit the needs of the plot – and yet, these character profiles feel accurately lifelike. It’s not surprising, given the efforts the Soviet cosmonaut programme put into personality testing, that they would aim to ‘design’ each Soyuz mission crew with the best fit of personalities to enable team-working. If so, interesting that the space programme is making similar choices to the needs of narrative?

Miss Shaw, at this stage, doesn’t need a Myers-Briggs as she’s not really there, and for the Quest structure, she is the ‘close friend’ who is ‘loyal to our hero, but doesn’t have much else going for him or her’ (sorry, Miss Shaw).

The tricky thing will be making my finale-heavy structure play out in the real timeline. But I think that’s where the emotional impact of the short version was, and will be, still Her final ordeal is a personal acceptance of, and struggle to, leave Mir to return home. Perhaps her obstacles are: winning Sergei’s respect, making her peace with death, coming home (both personal and personally dangerous). The final reward will come with Yuri Gagarin, but she needs to take that respect home with her.

Sunday March 22 2020 / Wednesday MAY 22 1991

Sunday March 22 2020 / Wednesday MAY 22 1991

Helen Sharman: Sets up and begins working through a series of 12 experiments; biological, chemical, crystallographic, photographic.

Me: Having built the structure and reorganised existing scenes, I start writing. I do a couple of hours before breakfast working through Act 1. The aim being to write in stages continuously for the next 4 days, following the time in which Helen Sharman is conducting the major experiments, winding up on 26th when she returned to earth.

I do a load of laundry go for a walk. Sit on my bedroom balcony in the sunshine drying laundry on a rack. After the draft is finished I hope to visit the beach before I go back home.

In the afternoon, the residency is halted because of the deteriorating situation over COVID-19. I peel off my post-its and drawings and ‘disappear’ my play from my workroom walls.

I go in my room, lie on the bed, and cry my eyes out….

That night Camilla, Fiona, Kirsteen and I eat dinner (Grace having left in the afternoon). The log stove is burning in the sitting room and we sit talking on our last night.

Nicola Baldwin sketch of Mir based on Helen Sharman diagram

Monday March 23 2020 / Thursday MAY 23 1991

Helen Sharman: Working through the experiments. Breaks off for live interview on TV am as Mir passing over UK.

Me: This is the day I part company with Helen Sharman, and head back down to earth. I wake up at half five and carry a chair onto the balcony up the cramped spiral steps from my room, to watch the sun rise. I think about space. The moon and earth. I think about ‘Overview’; Jeeva from UCL Outer Space Research Centre questioned Overview as a myth, despite some anecdotes from cosmonauts and astronauts about seeing our blue planet from space, being life-changing; it’s simply something the general public want to believe it true. I wonder about Helen Sharman’s last night on Mir, talking late with Sergei while the Sun rose and set rapidly during the circuit of an orbit. We know they talked about the journey back to earth, which is always more dangerous than launch and arrival. Perhaps they talked about the fact that Viktor and Musa – who would be returning with Helen on Soyuz TM-11, were making their first re-entry 5 months after they had trained for it, and that Helen – more recently trained in emergency protocols – would have a vital role to play, far beyond the responsibility of maintaining experiments on board. From what Helen Sharman has said of that conversation, it feels like she came to an acceptance of the possibility of death. That we all die, and cosmonauts are trained only for emergencies that are survivable, not how to prepare for those that aren’t.

We have breakfast together. Camilla sets off walking to the station, as the first to leave.

I remember a conversation with Fiona this week, on the relative merits of trying to force through a plan of work in a residency, or being open to what happens. Fiona – like Helen Sharman, a chemist by training – said that you can’t control what will happen or how you will feel, all you can do is observe the results.

Fiona packs her car and Kirsteen gets aboard for a lift to Glasgow. I wonder how Sergei Krikalev felt, as the Soviet Union vanished beneath him and the cosmonaut programme ground to a halt; no Soyuz crew could relieve them. Anatoli returned to earth in the final Soyuz. Sergei remained on board to maintain Mir. When he might return, no one knew.

I wave the others off in the sunshine and think of an interview with the senior psychologist at Star City, in which he said that if cosmonauts go into space and do not get along, when they return to earth they never talk to each other again; yet when cosmonauts on a mission get along well, they are friends for life.

The End?

I wrote this on the almost deserted 10.49 Arbroath to London train, 23 March 2020, the first day of national lockdown.

Wednesday March 25 2020 / Saturday MAY 25 1991 (London)

Wednesday March 25 2020 / Saturday MAY 25 1991 (London)

Helen Sharman: The 24th and 25th May were the two days in which I completed most of my work.

Me: These are the days I had intended to blitz-write the draft at Hopsitalfield based on the structures I had mapped out. Since arriving back in London on Monday night, I took yesterday off – to go out and buy food and get ready for the social distancing measures, until I can get back to Mir, and hope to use the next few days of isolation as a continued residency to finish the script roughly on schedule.

Nicola Baldwin, 25/3/2020

Thanks to my fellow Residents:

Camilla Brueton, Fiona McGurk, Grace Maran, Kirsteen Macdonald

Also:

Lucy Byatt, Hospitalfield Director

Cicely Farrer, Programme Manager

Earth, by Simon Faithfull (UCL Slade)

Posted on 24 September 2020

Earth-Spin – Simon Faithfull

My practice as an artist attempts to understand an individual’s relationship to the planet. Many of my works aim to drag our consciousness from the scale of the streets around us – out to the planetary scale of a rock spinning in space.

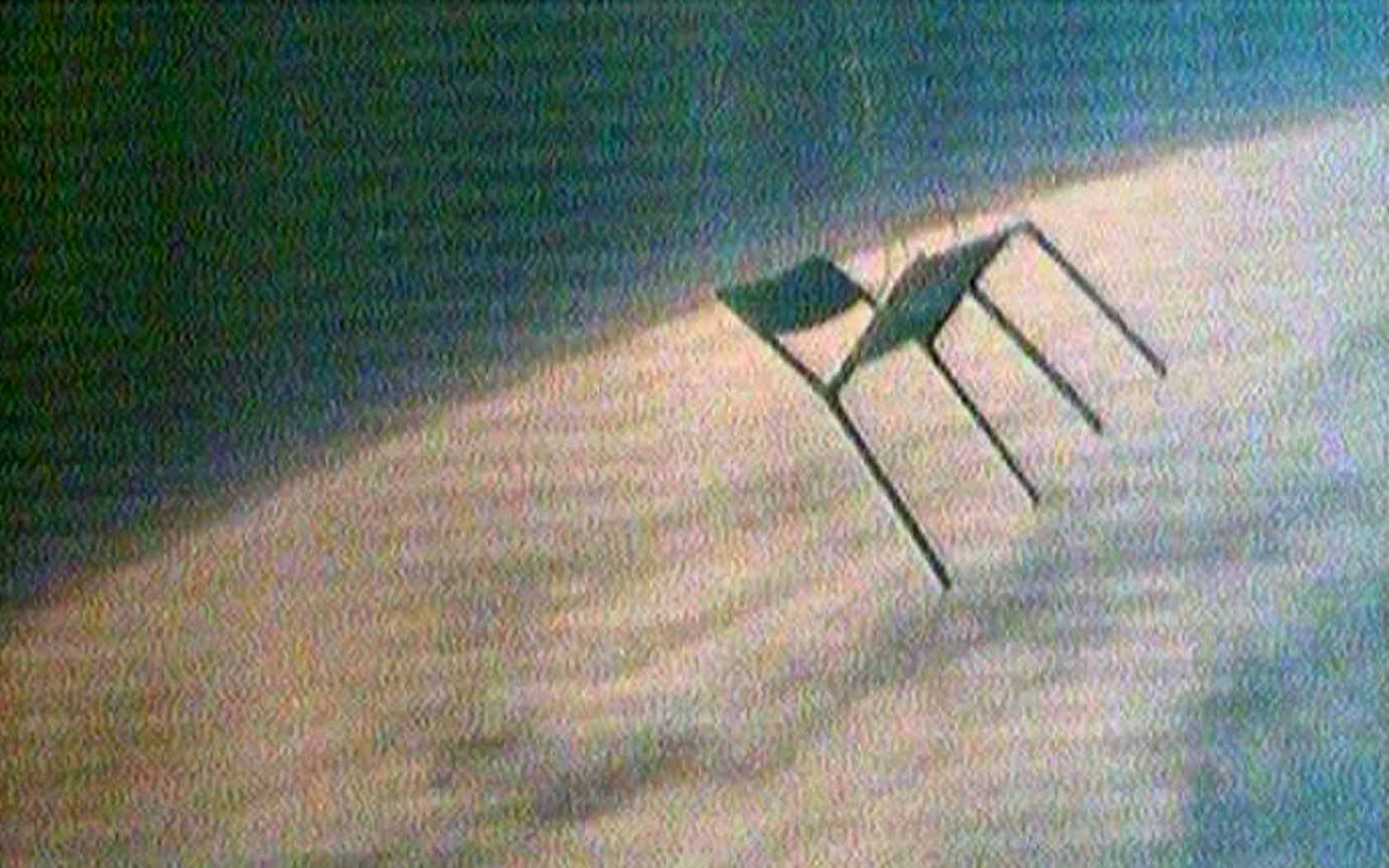

My video work: Escape Vehicle no.6 (2004 www.simonfaithfull.org/works/escape-vehicle-6/ )

…sent a domestic chair on a journey to the edge of space beneath a meteorological balloon. Behind the sky, at distance of only 30km, is the beginnings of black space.

Escape Vehicle no.6 – Simon Faithfull Commissioned by Arts Catalyst, Escape Vehicle no.6 started as a live event developed from the previous balloon film 30km. The live audience first witnessed the launching of a weather balloon with a domestic chair dangling in space beneath it. Once the apparatus had disapeared into the sky they then watched a live video relay from […] |

The more recent work: Earth-Spin #1: Graffenegg (2017 www.simonfaithfull.org/works/earth-spin-1/ )

…is an earthwork that seeks to destabalise the seeming stillness of a castle in Austria. Cut into the grass of the moat, two-meter-high letters spell out the speed at this lattatude, that the Earth’s surface is spinning through space.

Earth Spin no.1: Grafenegg – Simon Faithfull At the latitude of the Grafenegg in Lower Austria, the Earth’s surface is spinning through space at 1,108 Km/h – racing towards the eastern horizon in order in complete one rotation every 24 hours. Earth-Spin no.1: Grafenegg is a simple annotation of the planet Earth. Cut into the earth itself in two-meter high, 50 […] |

Finally Earthscape no.1: Wadi Rum (2018 www.simonfaithfull.org/works/earthscape-no-1-wadi-rum/ )

…as the world turns a figure is seen hanging from a lone tree in the desert of Jordan’s Wadi Rum. The four framed photos are hung so that the frames are touching to create the dizzying perspective of a planet spinning in space.

Earthscape no.1: Wadi Rum – Simon Faithfull As the world turns a figure is seen hanging from lone tree in the desert of Jordan’s Wadi Rum. The four photos are hung so that the frames are touching to create the dizzying perspective of a spinning planet. This photographic work was made whilst on a journey to find a boulder for the permanent […] |

Earth, by Dr David Jeevendrampillai, COSS Director

Posted on 24 September 2020

At its core, my academic work concerns the relationships people have to territory. I am interested in how people conceive of their relation to land in terms of how their sense of self, their identity, is tied to land, how they think through ownership, kin, belonging and politics. ‘Where are you from?’ is one of the most common questions one can be asked, how you answer this question expresses more than a geographic local but also how you think through your relationship to others, your sense of belonging and your sense of rights to place. Whilst in the past I have studied the anthropology of localism, in terms of people’s sense of relation and duty to their local area, I have wondered about the other end of the scale – the planetary.

In terms of the popular imagination, there has arguably been no more influential imagery than the photographs of the Apollo missions. On December 24th 1968, NASA astronaut Bill Anders, aboard Apollo 8, captured NASA image AS08-14-2383, a photograph popularly known as Earthrise. The image shows the ¾ illuminated Earth rising over the moon’s surface. It was described by nature photographer Galen Rowell as “the most influential environmental photograph ever taken”. The image is perhaps only matched by NASA image AS17-148-22727, or ‘The Blue Marble’, an image of the whole earth from 18,000 miles away, captured by the crew of Apollo 17 on December 7th 1972. These images of Earth are purportedly the most widely circulated and viewed photographic images in history (Poole 2008).

‘Earthrise’ NASA Image AS08-14-2383: Credit NASA

Whilst philosophers have long thought about the relation of humans to the Earth at the scale of the planet (see Oliver 2015) these images catapulted planetary thinking into the popular imagination, but not before they were altered slightly in order to fit particular psychosocial needs. As historian Benjamin Lazier (2011) points out, the original Earthrise image was orientated 90 degrees to the horizontal where the Moon loomed large to the right of the frame whilst the Earth was actually ‘setting’ behind the celestial body. This re-orientation of the frame places the Moon as a familiar terra, under the viewer’s feet and positions the Earth as coming into the light rather than disappearing from view. This reduces the disorientation that such images may engender in relation to established modes of thinking about dwelling on Earth, it places the viewer’s feet on the ground and privileges the Earth. The ‘Blue Marble’ image was also flipped so that Antarctica appeared at the bottom of the frame, not at the top as the original had it. This orientation and presentation of North reveals the preconditioned ways in which Earth is often viewed. These reorientations make the Earth familiar, palatable and usable in the mould of a particular Euro-American worldly vision.

‘Blue Marble’ NASA Image AS17-148-22727: Credit NASA

Such thinking on the imagery of Earth has been recently discussed by political philosophers, geographers and cultural theorists. Gayatari Spivak (2003) counters the term globalisation with the term confronting the Eurocentric narratives of Earth the images afford. Whilst Jazeel, who problematises the universalisms implicit in the narratives of ‘all mankind’ that often accompany the images, writes that decentring these images is “a wilful wrenching away from the desire to know with any degree of certainty or singularity the object depicted in AS17-22727 [NASA’s Whole Earth Image]” (2011:89).

However, as an anthropologist, these texts and thoughts on such imagery serve as a starting point to another form of inquiry. I ask who took these pictures, who changed their orientation and controlled their distribution. How do images of Earth from space work today? Images of planet Earth is a captivating aesthetic yet very view people are able to go to space and take this image. It is an aesthetic that is still very much filtered through the few space agencies and companies that can actually create such images. I would like to know the processes, selections and thoughts behind seeing the earth. What do people think they are doing when they are selecting ‘good’ images of Earth? I can not think of another source of imagery that has such an effect yet is created by so few. This intrigue will form the basis of the research I will be conducting as part of the UCL ETHNO-ISS project, which I have just joined.

It is often said that one of the great outcomes of the Apollo images was less our increased knowledge of the moon but the cultural and social impact of seeing the Earth from space. As Lazier notes such imagery has given rise to ‘globe talk’ through concepts such as globalism, global climate change, and global citizenship. The Earth might seem like a counter-intuitive place to start when talking about outer space, but it is because of Earth that we can say that there ‘space’ – not Earth. In the opening of the Centre of Outer Space Studies, I have invited some critical thinkers whose work I deeply admire. All of them in their own way consider the Earth in their artwork, playwriting or geological practice.

The COSS CATALYST events are designed to provoke an open and fun conversation across different disciplines with each event having a simple, deliberately vague theme. Please engage with the content below and join us for the live event on the 5th October.

Work Cited

Jazeel, T. (2011). Spatializing difference beyond cosmopolitanism: Rethinking planetary futures. Theory, Culture & Society, 28(5), 75-97.

Lazier, B. (2011). Earthrise; or, the globalization of the world picture. The American Historical Review, 116(3), 602-630.

Oliver, K. (2015). Earth and world: Philosophy after the Apollo missions. Columbia University Press.

Poole, R. (2010). Earthrise: How man first saw the Earth. Yale University Press.

Spivak, G. C. (2003). Death of a Discipline. Columbia University Press.

The Speakers

Simon Faithfull: at UCL Slade School of Fine Art

Faithfull’s practice has been described as an attempt to understand and explore the planet as a sculptural object – to test its limits and report back from its extremities. Within his work Faithfull often builds teams of scientists, technicians and transmission experts to help him bring back a personal vision from the ends of the world.

Divya M. Persaud: at UCL Mullard Space Centre

Divya M. Persaud is a planetary scientist, writer, and composer. With an ongoing focus in remote sensing for planetary geology and geophysics, she is completing her Ph.D. on 3D imaging and visualisation of the Mars surface at UCL’s Mullard Space Laboratory.

Nicola Baldwin: at UCL Institute of Advanced Studies and UCL Urban Lab

Nicola Baldwin is a writer for performance. She creates work on commission, in collaboration, on her own initiative – about love, friendship, science, space, politics, history, and the stupendous crises of ordinary life. She writes for theatre, radio, TV, film, installation, abandoned spaces, for audiences.

The Centre for Outer Space Studies (COSS)

Posted on 14 September 2020

The Centre for Outer Space Studies was founded in 2019 to promote research and teaching related to the social study of space and our relationship to the cosmos and the planet. The Centre aims to act as a catalyst for serious debate, via talks, exhibitions, film screenings and other events that help us explore the wider socio-political impact of space science and the wider human relationship to outer space.

This blog will be used for our COSS CATALYST events; each month during the term we invite three guest contributors to present work on a theme related to outer space. Themes might include for example ‘the body’, ‘environment’, ‘future’, isolation, etc. The guests range from scholars to professionals to enthusiasts. Each will be invited to contribute work that takes around 10 minutes to engage with. The work will be hosted here.

Close

Close