UCL research reveals secrets of superbug-busting antibiotic

12 October 2008

Links:

london-nano.com/" target="_self">London Centre for Nanotechnology

london-nano.com/" target="_self">London Centre for Nanotechnology

This week Nature Nanotechnology journal reveals how scientists from the London Centre for Nanotechnology (LCN) at UCL are using a novel nanomechanical approach to investigate the workings of vancomycin, one of the few antibiotics that can be used to combat so-called 'superbugs', such as MRSA.

The researchers, led by Dr Rachel McKendry and Professor Gabriel Aeppli, developed ultra-sensitive probes capable of providing new insight into how antibiotics work, paving the way for the development of more effective new drugs.

"There has been an alarming growth in antibiotic-resistant hospital superbugs such as MRSA and vancomycin-resistant Enterococci (VRE)," said Dr McKendry. "This is a major global health problem and is driving the development of new technologies to investigate antibiotics and how they work.

"The cell wall of these bugs is weakened by the antibiotic, ultimately killing the bacteria," she continued.

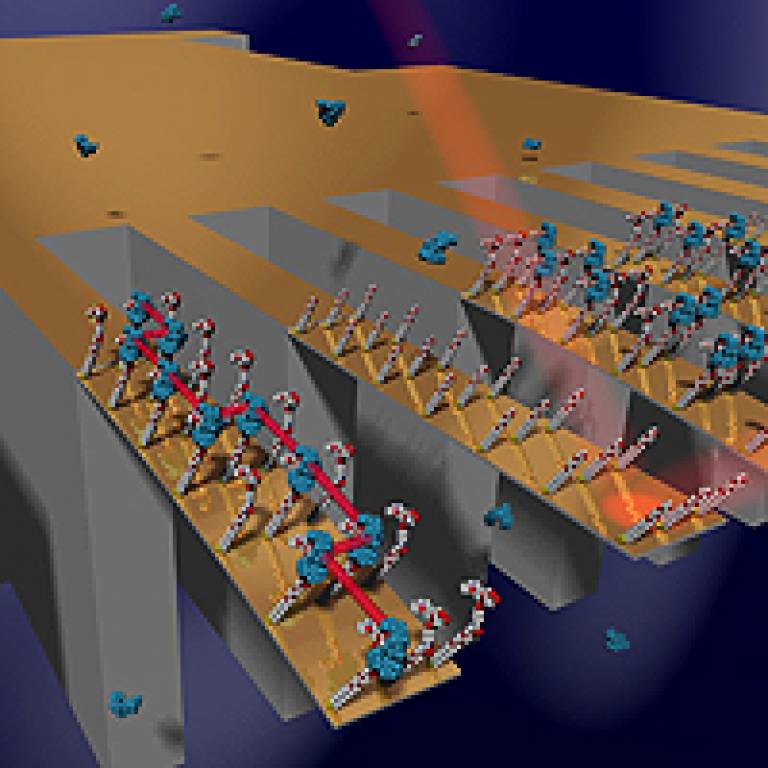

"Our research on cantilever sensors - tiny levers no wider than a human hair - suggests that the cell wall is disrupted by a combination of a local antibiotic and a polymer known as a mucopeptide binding together, and the spatial mechanical connectivity of these events.

"Investigating both these binding and mechanical influences on the cells' structure could lead to the development of more powerful and effective antibiotics in future."

During the study Dr McKendry, Joseph Ndieyira, Moyu Watari and co-workers used these cantilever arrays to examine the process that ordinarily takes place in the body when vancomycin binds itself to the surface of the bacteria.

They coated the cantilever array with polymers known as mucopeptides from bacterial cell walls and found that, as the antibiotic attaches itself it generates a surface stress on the bacteria, which can be detected by a tiny bending of the cantilever sensors.

The team suggests that this stress contributes to the disruption of the cell walls and the breakdown of the bacteria.

The interdisciplinary team went on to compare how vancomycin interacts with both non-resistant and resistant strains of bacteria. The 'superbugs' are resistant to antibiotics because of a simple mutation that deletes a single hydrogen bond from the structure of their cell walls.

This small change makes it approximately 1,000 times harder for the antibiotic to attach itself to the bug, leaving it much less able to disrupt the cells' structure, and therefore therapeutically ineffective.

"This work at the LCN demonstrates the effectiveness of silicon-based cantilevers for drug screening applications," says Professor Gabriel Aeppli, Director of the LCN.

"According to the Health Protection Agency, during 2007 there were around 7,000 cases of MRSA and more than a thousand cases of VRE in England alone. In recent decades the introduction of new antibiotics has slowed to a trickle but without effective new drugs the number of these fatal infections will increase."

The research was funded by the EPSRC (Speculative Engineering Programme), the IRC in Nanotechnology (Cambridge, UCL and Bristol), the Royal Society and the BBSRC.

Close

Close