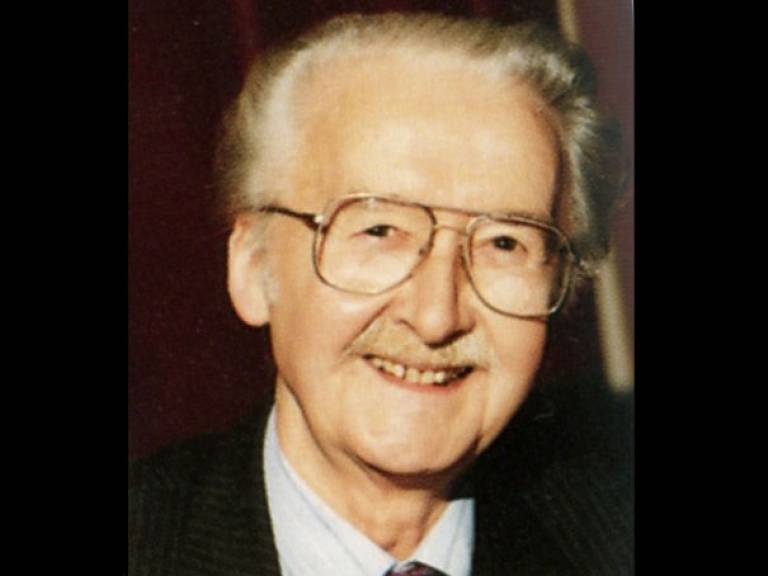

A tribute to Randolph Quirk, a "towering UCL intellect"

21 December 2017

The great British linguist, life peer and UCL scholar Baron Randolph Quirk has died at the age of 97.

He passed away on Wednesday night.

As a professor at UCL for more than 20 years, he revolutionised and shaped the study of English linguistics, becoming one of the most important figures of the 20th century in the subject.

Every student and academic who studies the English language will be aware of and will have been influenced by his seminal work into the written and spoken word.

He was also influential in shaping higher education in London as Vice-Chancellor of the University of London in the austerity years of the 1980s, played a key part in important public inquiries and committees and, in later life, was a passionate campaigner to improve the quality of education and training for the less fortunate.

UCL President & Provost Professor Michael Arthur, said: "We are sad to lose one of the great UCL academics, a man who shaped and inspired his discipline of English linguistics. He was also a passionate defender of education and played an important role in defining and securing the future of the University of London at a difficult time. He will be missed and our sympathies go to his widow and family."

Professor David Crystal, who worked with him on one of his most influential projects, the Survey of English Usage, said: "Randolph Quirk defined English language studies for the second half of the 20th century. I don't know of any English Language scholar who doesn't owe a debt to him because of everything he did. He has had that unparalleled influence."

Professor Bas Aarts, professor of English linguistics at UCL and current Director of the Survey of English Usage, said: "He was a towering intellect in the field. Anyone working in language studies will know his name."

Having been a junior lecturer at UCL until 1952, he returned as professor in 1960 before becoming Quain Professor of English Language and Literature in 1968, a post he held until 1981. He was responsible for two of the most important projects in English linguistics. One is the Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language, which is a seminal book on the subject, and the other is the creation of the Survey of English Usage in 1959.

The Survey was the first to sample written and spoken British English, between 1955 and 1985. A corpus of 1m analysed words, comprising 200 texts each of 5,000 words, it included dialogue and monologue, and written material intended for both reading and reading aloud.

The Survey was a crucial source of input to the Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language, the first major study of the real use of English in all its spoken and written domains.

He was Vice-Chancellor of the University of London from 1981-1985, and was president of the British Academy from 1985 to 1989. He was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in 1976 and was knighted in 1985. He became a life peer as Baron Quirk of Bloomsbury (the location for the campus of UCL) in the London Borough of Camden in July 1994 and was an active member of the Lords into his 90s.

Reviewing his life and achievements in 2001, he recalled his early upbringing on the family farm in the Isle of Man and how it made him "obsessively enamoured of hard work and to be just as obsessively sceptical about orthodoxies, religious or political."

This, he declared, was what made him such a "restless, free-ranging eclectic," something that proved a perfect fit for the radical, free-thinking liberalism of UCL. He noted that his Manx background, with its Celtic roots and Scandanavian influences, could also help explain his interest in language, history and language history.

"I came to UCL, eventually settling for the subject "English" because of the historical and linguistic bias in the curriculum," he said, although his early energies were diverted to the "lively" politics of the time (1939/40), music and "nights out with the girls."

His degree was interrupted by the Second World War when he served five years in the RAF's Bomber Command where he became so interested in explosives that he started taking evening classes for a degree in Chemistry at what is now Hull University.

After returning to UCL in 1945 to complete his degree, he became a junior lecturer at the university before being lured to Yale University on what is now a Harkness Fellowship. Travelling around the US brought him into contact with leading linguistic scholars before his return to the UK in 1952, and a post at Durham University.

He was less enamoured of doing his "amateurish best" to keep Durham's eminent tradition of Anglo Saxon scholarship alive than devoting himself to convincing students that "a linguistic approach could contribute valuable insights to the study of Shakespeare, Swift, Wordsworth, Dickens and all stations to TS Eliot and beyond."

It was here that the seeds of his dream of a survey of English usage were sown as he made frequent weekend trips to London where the BBC had given him a desk and free access to all their tapes and transcriptions of spontaneous speech.

Returning to UCL in 1960, he brought with him his "infant survey" where he credited the "unstinting" support from UCL, his department, successive Provosts, the British Council, Ford Foundation and brilliant colleagues for bringing to fruition one of the greatest projects on the English language for 100 years - the Survey of English Usage.

He was supported by Jan Rusiecki, who worked on the criteria for each linguistic decision, Professor Crystal, the lead partner in devising the scheme by which features of language were recognised and categorised, and Jan Svartvik and Henry Carvell, who beavered away, often through the night, on computational analysis. From that also came the Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language, which he put together with Geoffrey Leech, Sidney Greenbaum and Svartvik.

Though he was focused on his linguistics work, Baron Quirk found time to serve on Whitehall committees including the Lockwood report into examinations and a committee of inquiry that he chaired into speech therapy services, which he later noted revolutionised the service by making it an all-graduate career.

They were tasters for his elevation to Vice-Chancellor of the University of London (a job that he didn't apply for and was initially very reluctant to accept) in 1981. After years of growth, universities faced cutbacks and, in London, the university was hit by a 17% funding reduction spread over three years.

It was a difficult time when he faced protests from students but it was also a time when Sir Keith Joseph, then Education Secretary, lifted the veil for Baron Quirk on the parlous state of education in some inner city schools.

He recalled: "In one of my chilly confrontations in the Senate House with Sir Keith, he told me bluntly that if his department had the kind of money I was seeking, he wouldn't give it to me but to where it was infinitely more badly needed. "When were you last in any of our inner city comprehensives?" he asked.

"Well, the following week he took me to one for a couple of hours, and the scales fell from my eyes. In all my years as a university teacher….I was ashamed to realise that I had never bothered to find out what sort of quality education the majority of schools meted out. Well, ever since, I've been trying to make restitution in whatever way I could."

As President of the British Academy, he fought to improve the national curriculum and in the House of Lords, he raised the "disgracefully neglected" issue of the education and training of prisoners and young offenders.

Professor Crystal recalls a man who was inspirational and charismatic. After a first year of English language at UCL in 1959, Professor Crystal was in two minds about whether to continue because the quality of lectures were "not as enthralling as they might have been." Then Baron Quirk arrived.

"He came in in my second year. He gives one lecture and I was a convert. He blasted into the room," said Professor Crystal. "It was down to his magnetism, his enthusiasm and charisma. He had it. There's no question about it."

Baron Quirk's Survey of English Usage also transformed the landscape of linguistics. Until then, the subject had focused on formal kinds of English. Baron Quirk opened it up to a new range of writing and all kinds of speech including informal speech.

"It opened up innumerable dimensions to the subject. It was a breakthrough in the expansion of the subject. I don't know any modern English language scholar who hasn't read and not been influenced by it," said Professor Crystal.

Baron Quirk was also a kind and loyal man who would write unprompted to friends to wish them well. "He wrote a letter to me a month ago, completely out of the blue. 'Dear David,' he wrote. 'I am not so well.' He then expressed his affirmation of the work I have been doing. That was not unusual of him.

"All great scholars are very humble. He had that kind of humility."

Professor Aarts recalled taking a year out from his university in the Netherlands to spend a year at UCL, and entering the huge room where Baron Quirk would teach and "hold court." For a young undergraduate, it was both inspiring and daunting.

"He was such a towering intellect it was quite intimidating in a way. He could ask intimidating questions about particular aspects of the English language. People were in awe of him and a bit afraid of him," said Professor Aarts. Though he did keep on his room and happily allowed staff and students into it to make coffee while he worked away at his desk.

As Vice-Chancellor of the University of London and facing government reductions in funding, he instituted mergers that shaped higher education in London into what it is today including Bedford and Holloway (which became Royal Holloway), and Westfield and Queen Mary (which has become Queen Mary).

He faced criticism. Indeed, the student bar at University of London Union had been named Quirk's in recognition of him, but, was renamed by protesting students Mergers. Despite this, however, he did what he believed best for London and higher education as a whole, said Professor Aarts, and was passionate about it.

"After he became Vice-Chancellor, he went into the Lords and was very active into his 90s, so much so that he used to be a bit miserable during the summer because he couldn't go to the House as it was in recess."

Professor John Mullan, UCL's Lord Northcliffe Chair of Modern English Literature, said: "For all the years after his retirement, he continued to be an active presence in UCL and the English Department, for both of which he kept a strong affection. Many like myself who arrived after his official departure came to know him and to be stimulated by our exchanges with him."

He leaves a widow, Lady Quirk, nee Gabriele Stein, a German linguist and his second wife, and two sons by his first marriage, Eric and Robin.

Links

- An interview from 2001 with Baron Quirk on his life and works

- Background information on the Survey of English Usage

- Pictures from his time at UCL

- UCL English

Media Contact

Charles Hymas

Tel: +44 (0)20 3108 3843

Email: c.hymas@ucl.ac.uk

Close

Close