Vaginal bacteria linked to ovarian cancer

10 July 2019

Women at high risk of developing ovarian cancer have lower levels of protective “friendly” vaginal bacteria, as do women diagnosed with the disease, according to a new UCL-led study.

The study, led by the UCL EGA Institute for Women’s Health and published in The Lancet Oncology, found that changes in the amount of healthy bacteria, called lactobacilli, which normally help prevent overgrowth of other “unfriendly” types of bacteria, can be used to build a clearer picture of a woman’s risk of developing ovarian cancer.

The findings open up a new area of research which has the potential to lead to an easy and affordable indicator of ovarian cancer risk and risk-reducing interventions.

The study, jointly funded by leading gynaecological research charity The Eve Appeal and the European Commission Horizon 2020 initiative, used samples obtained from cervical screening.

Women with ovarian cancer, researchers found, had a significant reduction in vaginal lactobacilli. This significant reduction was also seen in women with a 40 times higher risk of developing ovarian cancer in their lifetime due to inheriting a BRCA1 gene mutation. The reduction in lactobacilli was more apparent the younger the women were, for both the women with ovarian cancer and the women at higher risk.

The research, led by Professor Martin Widschwendter (UCL EGA Institute for Women’s Health), is the first of its kind looking at the link between the type of bacteria in the vagina and development of ovarian cancer. It strongly supports growing evidence that the vaginal microbiome (type of bacteria) is important to health and that this under-acknowledged area of research needs more exploration.

The bacteria naturally found in the vagina create a protective barrier to infections, which stops them travelling up the gynaecological tract to the fallopian tubes and ovaries. If an infection does travel up the gynaecological tract, it can cause pelvic inflammatory disease, and lead to possible issues such as infertility. Evidence suggests that these infections can influence the development of ovarian cancer and other gynaecological issues. Professor Widschwendter’s study supports the theory that the protective lactobacilli bacteria are crucial in reducing the risk of developing ovarian cancer.

Further research hopes to demonstrate that re-introducing lactobacilli into the vagina will reduce a woman’s risk of the disease.

During the study, samples were taken from the cervix and vagina of 176 women who were eventually diagnosed with ovarian cancer, 109 women who were at high risk of developing ovarian cancer in their life time due to being carriers of an inherited BRCA1 mutation, and 295 women who were not at a higher risk of developing the disease. The samples were taken using a standard cervical screening brush, and were analysed using next-generation sequencing.

Young women at higher risk of developing ovarian cancer due to having a mutant BRCA1 gene had nearly three times less lactobacilli in the vagina compared with those who did not carry the mutant gene. The women within this group who also had a close family member with ovarian cancer were even more likely to lack lactobacilli.

Over a quarter of young women under the age of 30 with a BRCA1 mutation had low numbers of lactobacilli, whereas none of their peers without a BRCA1 mutation had reduced lactobacilli. Young women with a BRCA1/2 mutation are faced with difficult decisions concerning reducing their risk. Current cancer prevention procedures for BRCA1/2 carriers include a double mastectomy and removal of both ovaries and fallopian tubes at a young age, which reduces their lifetime risk of developing breast and ovarian cancer from 60-90% and 40-60% respectively to almost zero.

It is hoped that by monitoring changes in ovarian cancer risk over time, using lactobacilli as an indicator, young women with a higher risk of the disease will be able to make more informed decisions regarding the timing of cancer-prevention surgery (removal of the ovaries). This could allow women to postpone the surgery and preserve their fertility for much longer.

The next step in this investigation will be for Professor Widschwendter and his team to look into analysing whether “unfriendly” bacteria and any damage they cause are found at the fallopian tubes, the site where most ovarian cancers start. This will further inform our understanding of the different mechanisms which contribute to ovarian cancer, and support the use of bacterial changes in risk prediction and reduction.

Professor Widschwendter said: “This is a novel approach and could revolutionise the way that we can intervene and change the implications of being at high risk of ovarian cancer development. It’s the first time that we have been able to demonstrate that women with gene mutations have a change in their vaginal microbiome.

“The vision is to put this information together with other evidence emerging from our multi-strand research programme (FORECEE) and enable us to develop precise and informative risk prediction tests targeting several women’s specific cancers, including ovarian cancer.”

Athena Lamnisos, CEO of The Eve Appeal, said: “As a woman at high risk of cancer development you are currently faced with one stark choice – to undergo life-changing surgery to reduce your risk. This decision is not easy for many women, with implications for their fertility, being plunged into early menopause and the fact of undergoing surgery.

“This research is an exciting step forward in both understanding the factors that potentially impact on cancer development but also, and most importantly, in developing interventions that can reduce that risk. If that can be done by something as simple as adjusting the vaginal microbiome – that is a game-changer.”

This research falls into a broader programme FORECEE (4C, four cancers, one test), the aim of which is to develop a new test for the four main women-specific cancers. Currently the Widschwendter group are looking for women to take part in a programme called BRCA Unite. This study is looking to recruit women aged 18-45 years, with and without a BRCA mutation, and study the effect that changes in hormone, immune and microbiome profiles may have on supporting cancer development.

The team’s vision is to provide greater understanding of potential cancer-triggering factors and provide hope for future non-surgical alternatives as part of risk-reduction. If you wish to know more please contact their research team on 07741 670257 or via their website (www.brcaunite.org).

The research was led by the Department of Women’s Cancer at the UCL EGA Institute for Women’s Health, which is a joint venture between and University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (UCLH). It brings together individuals with expertise across the whole spectrum of women's health - from laboratory science to clinical skills to social and behavioural sciences - with the objective of making a major contribution to the health of women, both in the UK and internationally.

Links

- Full paper in the journal The Lancet Oncology

- Professor Martin Widschwendter’s academic profile

- UCL EGA Institute for Women’s Health

- UCL Women’s Cancer

- UCL Population Health Sciences

- The Eve Appeal

- European Commission’s Horizon 2020

Source

Image

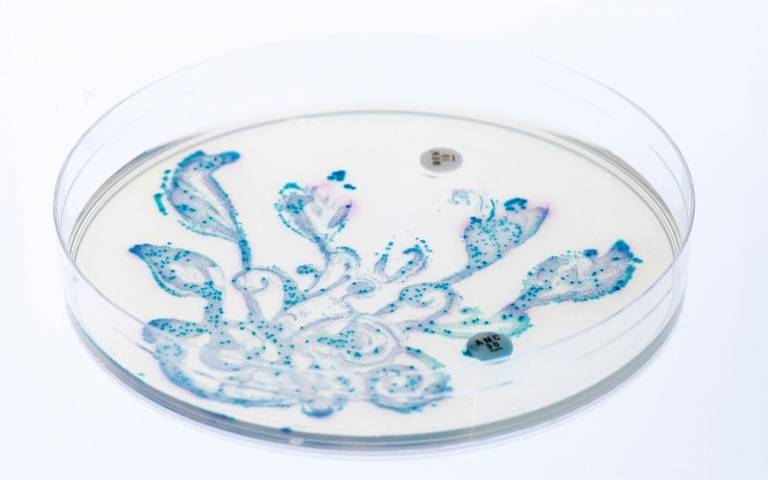

“Friendly” gut bacteria. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Credit: Dr Nicola Fawcett and Christopher Wood

Media contact

Rowan Walker

Tel: +44 (0)20 3108 8515

Email: rowan.walker [at] ucl.ac.uk

Close

Close