MANTRA

Increasing maternal and child health resilience before, during and after disasters using mobile technology in Nepal

9 January 2017

The Challenge for the Research

Perinatal women and their newborns are amongst the most vulnerable in disasters when access to healthcare advice and services may be reduced or non-existent. This project investigated hazard and risk perception, and building women's resilience by improving access to information and communications before, during and after disasters arising from geohazards. It aimed to do this by developing mobile technology to support and expand existing public health interventions and social protection mechanisms, especially in rural areas of Nepal.

We also covered day-to-day exposure to hazard - living and working in hazard-prone terrain. This initiative depended upon a transdisciplinary, gender-responsive, participatory and culturally-rooted approach to Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR), and maternal and child health. It combined geoscience and gendered DRR with participatory visual and textual maternal and child health care communications.

Overall Aim

To contribute to increase maternal and newborn health resilience before, during and after disaster using mobile technology

Background Context for the Research

There were many landslides and much road damage so people had difficulty reaching functioning health care facilities. While pregnant women and those who had newly delivered are high on the list of vulnerable groups, targeted services and responses were lacking or delayed. The collapse of birthing centres resulted in pregnant mothers having to travel further and with great difficulty, or opting for high risk home-delivery. The inability of the Female Community Health Volunteers (FCHVs) to get to these areas put lives in peril but they were dealing with their own damaged houses and family injuries at the same time.

Study Sites

KAVRE district was one of the most affected districts. Within that, we chose two VDCs: Chyamrangbesi and Chandenimandan.

| Chyamrangbesi VDC | Chandeni Mandan VDC |

Very steep and deep valley Remote, borders Lalitpur district Many damaged houses but few homes collapsed Few deaths. Injuries mostly minor High risk of landslide/ rockfall High risk of lightning strikes Occasional flash floods | Less steep but has large altitude range Less remote, borders Indrawati River and Sindhupalchowk district Nearly all homes collapsed Numerous deaths and injuries (buried in rubble) Moderate risk of landslides/rockfall Flood risk from rivers |

Our approach to Geohazard Assessment included: Remote sensing; review of previous geohazard work (esp NRA/UNOPS post 2015 Hazard Assessment); field observations and discussions; geohazard interface with communities.

Methods of communicating hazard included: a mobile phone app in a game format (see below); annotated photographs; and video demonstrations.

Film and Photo Voice

- Goma: https://youtu.be/yKUxNOn4OLQ

- Bimala: https://youtu.be/urv3WyKI9Oc

- Apsara: https://youtu.be/jx8xecaQBSU

Dinesh also created 11 photo voice presentations which comprised each of the 11 women’s stories told in their own voice (original language and translation) and two photographs each, showing the woman herself plus a significant image that she selected for photographic record.

These were exhibited (visual and audio) in Kathmandu and project partner HERD International is taking the materials back to the communities.

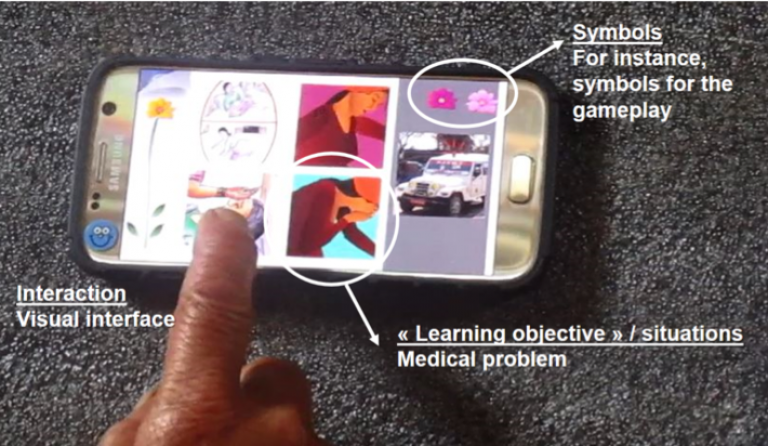

MANTRA - Serious Mobile Game App

Because communication before, during and after earthquakes and landslides was a major difficulty, we aimed to provide educational content as learning through gaming. This can be beneficial for engagement and immersion. The app was designed with 3 modules: maternal health, neonatal health and geo-hazards. It was particularly challenging to build a prototype app in just a few months but this was achieved through solid team effort.

App Requirements

The app was aimed at a particular target audience:

- Low or no education;

- Not smart phone users;

- Not gamers.

Therefore, the game had to be designed with:

- No text (for those unable to read);

- No voice (for technical reasons this was not possible under tight time constraints);

- Intuitive interaction with the phone because written help could not be included;

- A tutorial for Drag and Drop (for those unfamiliar with smart phones);

- Culturally appropriate graphic design.

The app was designed and then tested in focus group discussions (FGDs) with women in Kathmandu and in our study communities. The team then made changes to the app and tested again. Evaluations included 50 participants whose ages ranged from 20 to 60. They comprised two key groups: FCHVs (24 participants); and Community women (26 participants). Learning through gaming provided evidence of increased learning for many objectives. The women enjoyed the process of using the app and even the older age group of women who had never used a smart phone before engaged with the app and learned from it. There are many more refinements that can be made in the next phase of research. Qualitative Research in two Communities The research used qualitative focus group discussions (FGDs) and in-depth interviews, to provide: · Detailed insights on risk knowledge and understanding; · Health and other needs at the time; and · Opportunities to strengthen readiness to respond during humanitarian emergencies. Although women knew of geohazards and risks, many did not know that an earthquake of that magnitude might happen. Neither did they know what to do if one did occur. They were beset by confusing (and dangerous) guidelines. For example,the widely practised ‘duck, cover and hold on’ was a killer rather than a saviour in poorly constructed houses. The women told their stories of struggling to walk long distances on steep slopes to reach hospital while in labour; they told of giving birth on the floor in damaged hospitals without beds; of living outside for days without food and little water which led to their breast milk drying up and their newborn babies suffering; of having no clothes for themselves or their babies to change into and no sanitary supplies; and of desperately needed services arriving only days or weeks later.

Evaluations included 50 participants whose ages ranged from 20 to 60. They comprised two key groups: FCHVs (24 participants); and Community women (26 participants). Learning through gaming provided evidence of increased learning for many objectives. The women enjoyed the process of using the app and even the older age group of women who had never used a smart phone before engaged with the app and learned from it. There are many more refinements that can be made in the next phase of research.

Qualitative Research in two Communities

The research used qualitative focus group discussions (FGDs) and in-depth interviews, to provide:

- Detailed insights on risk knowledge and understanding;

- Health and other needs at the time; and

- Opportunities to strengthen readiness to respond during humanitarian emergencies.

Although women knew of geohazards and risks, many did not know that an earthquake of that magnitude might happen. Neither did they know what to do if one did occur. They were beset by confusing (and dangerous) guidelines. For example,the widely practised ‘duck, cover and hold on’ was a killer rather than a saviour in poorly constructed houses.

The women told their stories of struggling to walk long distances on steep slopes to reach hospital while in labour; they told of giving birth on the floor in damaged hospitals without beds; of living outside for days without food and little water which led to their breast milk drying up and their newborn babies suffering; of having no clothes for themselves or their babies to change into and no sanitary supplies; and of desperately needed services arriving only days or weeks later.

Conclusions for planning a disaster response for perinatal women:

- Have ready-made plans to prioritise perinatal women and newborns;

- Ensure medical care in the community, as well as available and affordable/free transport to health facilities;

- Provide special items for pregnant or newly delivered women and their babies (clothes, pads, nappies, hygiene kits) in a timely manner;

- Provide safe shelter;

- Provide the special food for pregnant or newly delivered mothers which accords with local cultural practices;

- Make psychosocial services available;

- Provide creches for other children in the family to reduce mothers’ anxieties;

- A rapid response is vital especially when women are in labour or about to be.

Deliverables and Outputs

Our planned deliverables (all met) included:

- Developing appropriate language and terminology for use by laypersons; and collaborating with a local expert geologist;

- Collating local health and environmental risk knowledge, stories and experiences from women and FCHVs for sharing locally and exhibiting more widely, including as content for the pilot app;

- Developing a pilot app and testing with local women; and

- Sharing findings through exhibitions (locally, in Kathmandu, and London) and Networking Workshops (Kathmandu).

The Networking Workshop and exhibition in Kathmandu provided positive feedback on the work. Participants especially appreciated the use of local languages in the films and photo voice stories. We are also working on a networking workshop in London and a series of journal articles.

Close

Close