Humans evolved from all across Africa

23 September 2019

Modern humans evolved in Africa, and groups from all over the continent contributed to that process, so we should stop searching for a single point of origin, according to researchers led by UCL and the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

In a comment paper published in Nature Ecology and Evolution, the researchers argue that our evolutionary past must be understood as the outcome of dynamic changes in connectivity, or gene flow, between early humans scattered across Africa.

Viewing past human populations as a succession of discrete branches on an evolutionary tree may be misleading, they said, by simplifying the human story to a series of ‘splitting times’.

“The genetics of contemporary humans are very clear. The greatest genetic diversity is found in Africans,” said the study’s senior author, Professor Mark Thomas (UCL Genetics Institute).

“The old theory that we descend from regional populations spread across the Old World over the last million years or so is not supported by genetics data.

“Non-Africans today have some ancestry from Neanderthals, and some have appreciable ancestry from the recently discovered Denisovans – and maybe other, as yet undiscovered ancient hominin groups. But none of this changes the fact that more than 90% of the ancestry of everybody in the world lies in Africa over the last 100,000 years.”

The researchers point to previous studies estimating that Neanderthals contributed just 1.5-2.8% of the genetic makeup of non-African people, while the more recently discovered Denisovans contribute 0.3-5.6% to East Asian and Oceanian people’s genetics.

Professor Thomas continued: “Knowing that we are an African species has led many to ask the question ‘where in Africa’. But when we consider the genetic patterns alongside what we know of fossils, ancient tools, and ancient climates, the ‘single region of origin’ view just doesn’t cut it, and we have to start thinking differently.”

The researchers advocate a structured population model, as humans evolved from multiple interconnected subpopulations of early humans, spread out across Africa in a large metapopulation. A structured model reflects a continuous process of fission, fusion, gene flow and local extinction.

Lead author Dr Eleanor Scerri (Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History) said: "We see physically diverse early human fossils from across Africa, some very old genetic lineages and a pan-African shift in technology and material culture that reflects advanced cognition, including new technical and social innovations, across the continent. In other words, what you'd expect from a dynamic interconnected patchwork of populations that were at times more or less isolated from each other."

Co-author Dr Lounès Chikhi (University of Toulouse and Gulbenkian Institute of Science in Lisbon), added: "Instead of a series of population splits branching off an ancestral tree, changes in connectivity between different populations over time seem a more reasonable assumption, and appear to explain several patterns of genomic diversity not explained by current alternative models.

“Metapopulations are the kind of model you'd expect if people were moving around and mixing over long periods and wide geographic areas. We cannot objectively identify this geographic area today from genetic data alone, but data from other disciplines suggest that the African continent represents the most likely geographical scale," he added.

The authors say the scientific community may finally have the means to address complex questions in human evolutionary studies that could not be addressed previously.

"A metapopulation model helps us to find a way to acknowledge the paleontological, archaeological and genetic evidence for a recent African origin with limited gene flow from non-African metapopulations, such as Neanderthals,” Dr Chikhi said.

The scientists argue that this view is not only better supported by the fossil, genetic and archaeological evidence, it also better explains the palaeoanthropological record beyond Africa.

"We see physically diverse early human fossils from across Africa, some very old genetic lineages and a pan-African shift in technology and material culture that reflects advanced cognition, including new technical and social innovations, across the continent. In other words, what you'd expect from a dynamic interconnected patchwork of populations that were at times more or less isolated from each other," Dr Scerri said.

Links

- Research paper in Nature Ecology & Evolution

- Professor Mark Thomas’ academic profile

- UCL Genetics Institute

- UCL Genetics, Evolution & Environment

- UCL Life Sciences

Image

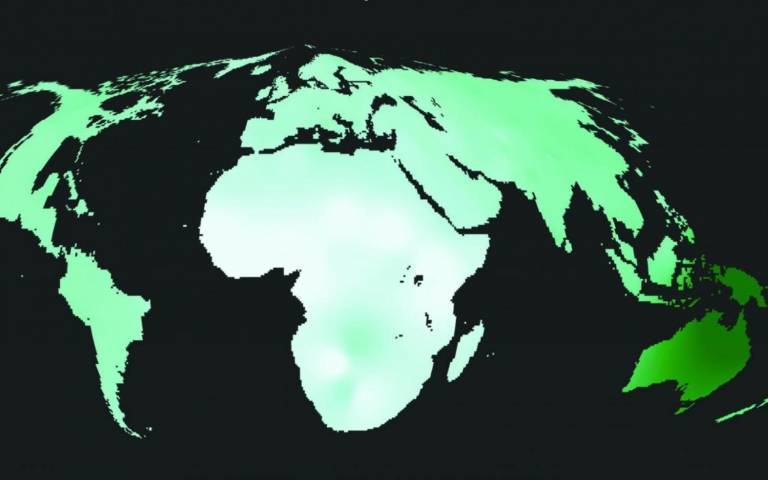

- World map with land area resized to represent modern human genetic diversity, and colour representing Neanderthal plus Denisovan ancestry (darker green represents up to 8% Neanderthal + Denisovan ancestry). As can be seen, contributions from other populations to the Homo sapiens gene pool are small and unevenly distributed. Africa is disproportionately large because the great human genetic diversity – and hence the roots of humanity – are found here. Cartogram produced by Dr James Cheshire (UCL Geography) with Professor Mark Thomas.

Media contact

Chris Lane

tel: +44 20 7679 9222

E: chris.lane [at] ucl.ac.uk

Close

Close