Obituary: Robert Burton Pynsent (1943-2022)

4 January 2023

We are saddened to inform you that Robert Pynsent, Emeritus Professor of Czech and Slovak Literature has passed away.

SSEES Professor Emeritus of Czech and Slovak Literature Robert B. Pynsent died this past Wednesday, 28 December, at age 79. Robert arrived at SSEES in 1972 and soon became a towering figure in the institution and in his field, both through his rigorous scholarship and his inspirational character. Over his career he profoundly influenced generations of students and scholars, both in the U.K. and abroad, through the example he set of what it was possible to achieve as a literary historian and critic. Fiercely dedicated to his students and an inexhaustible interlocutor, he was sought out by professional colleagues and friends long after his retirement in 2009. Those who knew him learned enormously about those rarest of human qualities: genuine originality and integrity.

Robert’s erudition was, quite simply, otherworldly. No one who spent any time with him could think of Czech and Slovak as ‘small’ literatures. His expectation was that a Bohemist (yes, that is what those in the field are called) must read and know everything written in Czech and Slovak from the first emergence of the vernacular literatures in the late 13th century up to and including the significant publishing events of last week. (Fluency in ‘major’ traditions such as German, French, British, Classical and Biblical, as well as ‘neighbouring’ traditions such as Polish and Hungarian, went without saying.) The standards he set seemed utterly unrealistic—except that he held to them himself, to the astonishment of all who met him. Robert drew on this vast knowledge to produce insights and opinions that often went quite contrary to accepted narratives about which authors were and were not ‘great’, or which developments were and were not ‘important’, and he often irritated those whose revered beliefs he questioned. But Robert’s proclamations were never mere provocations: they were rather a call to do the work and to think for oneself. Nothing would more quickly produce his characteristically warm smile than a well reasoned challenge to his own views.

While seeming to know everything about Czech and Slovak literature, Robert did show particular interest in certain subjects: 14th-century Czech literature (he argued that the subsequent Hussite period, generally eulogized as a ‘heroic’ period in the history of Bohemia, had been a catastrophe for Czech-language literature); the literature of the Baroque period (he argued that the ideological scheme portraying German cultural dominance over and oppression of Czech culture in this period was an ignorant distortion); the great Czech Romantic Karel Hynek Mácha (about whom he produced essential interpretive studies); Czech Decadence (which he argued was as innovative as western European Decadence movements); 20th-century Czech women authors (among whom he found voices far more talented than some of their lionized male peers); and postwar Slovak literature (for which he proposed an entirely original interpretive template). For those working on Czech and Slovak literature, it is a challenge to keep up with Robert’s work in any one of those areas.

Robert was one of the purest representatives of an intellectual culture at SSEES that has been withered by the bureaucratization of the modern university. The door to his smoke-filled, top-floor office on Russell Square was always open, with students dropping in and often staying for hours talking of all things Czech and Slovak. Among his course offerings was, for example, a year-long seminar on 14th-century Czech literature. As if that weren’t enough, Robert led weekly Literature Seminars in the evening, where in addition to their coursework students read works of Czech and Slovak literature (often hefty tomes of many hundreds of pages, all untranslated of course), gave presentations, discussed, argued—again, ensconced in smoke from bottomless packs of cigarettes and refreshed by a bottle or two (or more) of alcohol. A different era, to be sure; but one whose spirit of excitement and devotion to field remains inspiring. The intellectual energy Robert tapped was generated from the conviction that no matter how much one read, it was never enough.

In academic circles Robert had an at times fearsome reputation. He often veered dramatically from convention and he defended his views uncompromisingly and with bewildering learnedness. He knew so much he would draw connections that could strike others as brazen—though the more one listened the more the connections became difficult to deny. He debated sharply, though behind this lay a deep and disarming sense of humour. In a footnote in the published version of a paper he once gave at a conference, Robert noted that a disgruntled colleague in the room had objected not only to his argument, but also to his hair—on the grounds that both were ‘disorganized’. Oh, to have been there…

His iconoclasm fascinated many but repulsed others. Perhaps no position Robert took had as great a public resonance as a letter that he (and two other colleagues, though the tone was characteristically Robert’s) published in The Times after the Czech poet Jaroslav Seifert received the 1984 Nobel Prize. The letter claimed that Seifert, a signatory of Charter 77 who at the time was highly regarded in Czechoslovak dissident circles, was in fact a mediocre poet—with the exception of his early career when he had been a committed Communist. This struck at many sacred cows, and to this day there are circles for whom the six sentences making up that letter seem effectively the only thing that Robert ever wrote, and are taken to have shown ill will towards Czechoslovakia during a very difficult period. One can debate the prudence of that letter in the given circumstances, but no one who has looked into even a fraction of the thousands of pages of scholarship Robert produced on Czechoslovak culture can have any doubt as to his ethical and cultural commitments. He held that Czech literature had for centuries ‘punched above its weight’, and he became impatient when Czechs referred to themselves self-deprecatingly as a ‘small nation’ or ‘minority culture’. But he had an instinctive distrust of anything that smacked of mythologization or unthinking self-satisfaction: hence his critical attention to figures such as Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk, the widely idolized president of the first Republic of Czechoslovakia after the First World War, and his countering of the deeply rooted ideology of Czech culture’s ‘natural’ instincts for democracy and tolerance by researching and revealing the vehemence of antisemitism in Czech and Slovak culture.

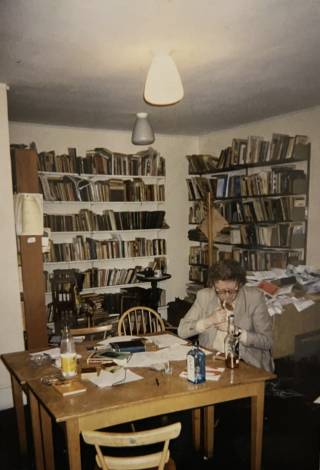

After his retirement Robert rarely came in to London, but his home in Speldhurst in Kent—a beautiful, quirky old house with a beautiful, spacious garden—became practically a pilgrimage site for those in the U.K. with interests in Czech and Slovak, and Robert was always a generous host. Those rambling, dusty rooms were filled with books, books, and more piles of books, on groaning shelves, covering the chairs, seemingly growing out of the floors: a labyrinth and a memory palace in which one would get lost until Robert traced a path and showed some order. It is easy to think those paths are now lost forever, and to feel bereft; but the legacy Robert would want is for us to discover new ones on our own.

We have lost one of the best among us.

Written by his close friend, Dr Peter Zusi.

Close

Close