3 Anti-presuppostion Theory

Sauerland (2003), (2008b) and Sauerland, Anderssen, and Yatsushiro (2005) propose that the plurality inference of a plural noun phrase is an anti-presupposition that is generated in competition with the singular.

3.1 Anti-presupposition

-

Sam thinks that I am Cambodian.

↳ I am not Cambodian. -

Chris invited all of his supervisees to his place.

↳ Chais has more than two supervisees.

These inferences are considered to be triggered via competition with alternative expressions with stronger presuppositions (Heim 1991; Percus 2006, 2010; Sauerland 2008a; Spector and Sudo 2017; Marty 2017).

-

Sam knows that I am Cambodian.

↳ I am Cambodian. -

Chris invited both of his supervisees to his place.

↳ Chais has exactly two supervisees.

Maximize Presupposition!

An utterance of φ is infelicitous in context c if φ has an alternative ψ such that:

- the presupposition of ψ asymmetrically entails the presupposition of φ;

- the presupposition of ψ is satisfied in c; and

- the assertive meanings of φ and ψ are contextually equivalent in c.

In contexts where the presupposition of Example 3.2a is satisfied, Example 3.1a is infelicitous. In other contexts, it is usable. So, although Example 3.1a has no presuppositions in the semantics, it has a presuppositional requirement that the presupposition of Example 3.2a is not satisfied.

3.2 The plurality inference as an anti-presupposition

Sauerland and his colleagues’ idea is to make use of Maximize Presupposition to account for the plurality inference. For example:- The problem is easy to solve.

- The problems are easy to solve.

- Example 3.4a presupposes that there is only one problem.

- Example 3.4b only presupposes that there is at least one problem.

So Example 3.4a has a stronger presupposition than Example 3.4b.

If it is commonly known that there is only one problem:

- the presupposition of Example 3.4a is satisfied

- the assertive meanings of the two sentences are identical.

Therefore, Example 3.4b cannot be felicitously used.

Conversely, if it is commonly known that there is at least one problem but it is not commonly known that there is exactly one problem, Example 3.4b should be usable. There are two such contexts:

- It is commonly known that there is more than one problem.

- It is commonly known that there is at least one problem, but it is not commonly known exactly how many.

Context: It is common belief that Paul either wrote exactly one song or several songs.

- #The song is good.

- #The songs are good. (Mayr 2015: p.211)

- #If Paul wrote either several songs or just one, the new song is good.

- #If Paul wrote either several songs or just one, the new songs are good. (Mayr 2015: p.212)

- Every applicant submitted their experimental paper in their submission.

- Every applicant submitted their experimental papers in their submission.

Example 3.7a presupposes that every applicant has exactly one experimental paper. The anti-presupposition of Example 3.7b will be that this presupposition is not satisfied (and it presupposes that every applicant has at least one experimental paper). One such typical context is one where some of the applicants have multiple experimental paper.

3.3 The problem of quantification

Another problem arises with existential quantification. To see this, let’s delve into the details of Sauerland’s (2003) theory.

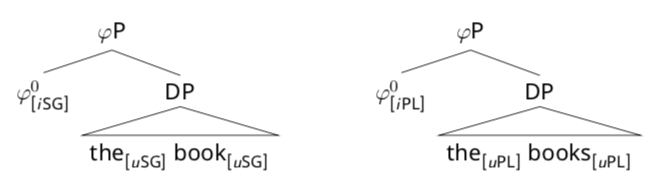

φ-features are always interpreted right above DP.

Nouns themselves are always semantically number neutral.

The definite article the triggers an existential presupposition that there is at least one entity satisfying the NP extension and picks out the unique maximal such entity.

- 〖[iSG]〗 = λx: x is an atomic entity. x

- 〖[iPL]〗 = λx. x

every paper λx [ Greg read [φP [iSG] x ] ]

Given that a universal quantifier generally gives rise to a universal presupposition in this configuration, this sentence should presuppose: every paper is an atomic entity.

Sauerland (2003) assumes that indefinites are existential generalized quantifiers and trigger existential sentences with respect to the presuppositions of their scope (Heim 1983; Beaver 2001; Chemla 2009; Sudo 2012).∃(R)(S) presupposes there is x in R that satisfies the presupposition of S.

Cf. ‘An Italian linguist crashed his Ferrari’ seems to presuppose only that there is an Italian linguist who had a Ferrari, rather than, e.g. that every Italian linguist has a Ferrari.

But this gives rise to an issue for plurality inferences.-

I saw horses.

[∃ horses] [λx I saw [[iPL] x]]

Presupposes: ⊤ -

I saw a horse.

[a horse] [λx I saw [[iSG] x]]

Presupposes: There is an entity that is an atomic horse.

Since the plural feature has no presupposition, Example 3.11a has no presupposition (I ignore presuppositions like that horses are visible, that the speaker exists, etc. here to simplify the exposition), so Example 3.11b has a stronger presupposition. Sauerland’s prediction, then, is that Example 3.11a is only usable when it is not commonly known that there is a horse. However, this does not seem correct. Example 3.11a is perfectly fine, even if it is commonly agreed that there are horses.

Notice also that it does not help to assume that 3.11a has an existential presupposition that there is an entity that is an atomic horse or a plurality of hourses, because this is actually equivalent to the presupposition of 3.11b.

To circumvent this problem, Sauerland (2003) stipulates that with an existential quantifier, Maximise Presupposition is calculated within the nuclear scope.- [I saw [iPL] x]

- [I saw [iSG] x]

Example 3.12a is only usable if the presupposition of Example 3.12b is not satisfied, i.e. when it is not commonly known that x is not known to be atomic. Then Example 3.11a will be usable if there is an atomic unicorn or a plurality of unicorns that is not known to be atomic.

However, this solution is not good enough, as Sauerland, Anderssen, and Yatsushiro (2005) point out. The assumption that the singular feature is a presupposition trigger already makes a bad prediction for negative sentences.

I didn’t see a unicorn.

LF: not [a unicorn] [λx I saw [iSG] x]

Given that negation is a presupposition hole, this should presuppose that there is an atomic unicorn!!

Sauerland, Anderssen, and Yatsushiro (2005) instead claim that ∃(R)(S) has no presupposition (cf. Kadmon 2001) and only asserts ∃(R(x) & S(x)). But then there is no presupposition for Example 3.13. However, then we have lost an explanation for the plurality inference.

Note that we cannot explain it as a scalar implicature, because the following two statements are equivalent.- There is an atomic unicorn.

- There is an entity that is an atomic unicorn or a plurality of unicorns.

3.4 Summary

Sauerland (2003), (2008b), and Sauerland, Anderssen, and Yatsushiro (2005) pursue the idea that φ-features are presupposition triggers. But there are two problematic predictions:

- Definite plurals should be acceptable in ignorance contexts.

- Plurality inferences in existential constructions.